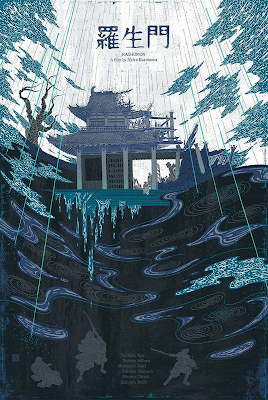

The first

film in my analysis of the Chambara films of Akira Kurosawa, is the nonlinear

masterpiece Rashomon. One of the load bearing films in Kurosawa’s

Filmography that contributed to his overall international success, Rashomon fundamentally

changed the way films were conceived, shot, edited, while motivating

generations of future filmmakers to

attempt this style of filmmaking, some with more success

than others. Regardless of their success

or failure, Rashomon is undeniably a creative masterwork and what many

have believed to be one of the greatest films of all time. This essay is taking

a slightly different approach by looking at the film through the prism of a

post war Japan: its crisis of national identity amongst its people, and an

analysis of gender and cultural norms that results in the fluidity and fallibility

of personal experience; that is as Kurosawa points out, unreliable.

PLOT

A peasant seeks shelter

from the rain under a dilapidated Rashomon (Gate) between Kyoto and Nara in 11th

century Japan. There, he meets a priest and a woodcutter, who begin to recount

a chance encounter between a bandit, a Samurai, and his wife. As we hear

different versions of what happened from all participants, the actual events

get obfuscated. In the end, it is left up to the peasant (as the audience

surrogate) to decide which single version or combination of the story is true,

if there is truth at all.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Kurosawa’s Rashomon is

based upon the short story “In the Grove”, by Ryunosuke Akutagawa in 1922; adapted

by himself and screenwriter Shinobu Hashimoto. Kurosawa decided to do the film

after the lukewarm reception to his anti-yellow journalism film Scandal, distributed

by Sochiku pictures. At that time, Daiei Films approached him with another

offer to direct. The pitch for Rashomon was accepted primarily due to

its lower budget and assumed simplicity.

Yet, upon closer examination, the film is retrospective of a country going

through an existential crisis after its major military defeat during World War

II.

According to Akiko Hashimoto

(2015), the historical and cultural trauma that Japan experienced through their

defeat at the end of World War II, is often processed through popular culture[1]. This form of cultural

trauma (manifested in three categories of heroes, villains, and perpetrators) presents

defeat as a part of Japan’s national identity. The result of this is the lack

of collective memory, and the meaning of being Japanese (Hashimoto 2015). The framing of Rashomon as a triptych structure

with intentional contradiction, is a representation of that trauma (Davidson 1987).

The four different stories that we hear in the film, and their differences, can

be compared to the experiences of various traumas people experience during the war,

such as the different ‘Vantage Points’ during the bombings of Hiroshima and

Nagasaki. This left a collective social, political, and moral scar on the

Japanese people that would haunt them for over half a century.

After the resounding

defeat of World War II, there was both a sense of moral urgency and artistic

ambition. Many of the films of the beginning of the post war period in Japan

(including Kurosawa’s earlier work) “illuminated the confusion and despair of

the period and offered narratives of personal heroism as a model for social

recovery…to pursue a legacy of hope for a ruined nation.” (Prince 2012: 8). Rashomon

wrestles with these ideas as it presents four vastly different and

contradictory accounts of events; and then, has three men debate their veracity.

The questions of “Who to believe?”, and “Who is at fault?” plays into how each

character (and by extrapolation, the collective memory of Japan) decides what

really happened, despite evidence.

Production

When he was hired, Director

of Photography Kazuo Miyagawa was surprised that Kurosawa was short in his

conversations with him; not really guiding the positions of the camera nor

having discussions of the shot composition.

In an interview for the Criterion Collection Blu-ray, Miyagawa states

that he took Kurosawa’s terseness, as a challenge; believing the director

wanted him to demonstrate his cinematography skills. This was the motivation behind the tracking

shot of The Woodcutter through the forest. A shot which would go on to

revolutionize filmmaking, in just one afternoon.

If one is ignorant about

the nuances of film production, the forest shot may seem simple. A man walks

through the woods with an axe resting on his shoulder, the camera then cuts to

a shot of the covered axe blade, and then a closeup on the face of the

woodcutter. Basic. However, as the camera drops back behind him, we are treated

to a dolly tracking shot that suddenly defies logic. Because the camera and the

actor are moving in different directions at the same time, the audience cannot

clearly tell when the Woodcutter is going left or right; abruptly being treated

to sweeping camera angles without a single cut. The dolly track was set around

this hilly landscape in a configuration that represents the infinity symbol.

Additionally, not only is Miyagawa utilizing unconventional shots, (look at the

shot of the woodcutter as he moves across the log) but he is also experimenting

with shots that have never been conceived.

Lighting

Before this film, there

was the cinematic rule that you could not shoot directly at the sun. The reason

being the exposure of the film to the sun’s rays, would ultimately destroy

it. Miyagawa, seeking as much natural

light as possible, figured out if you close the shutter after a certain time, you

both save the film and get an amazing shot of the full sun in the sky.

Additionally, shooting on location among actual trees, allowed Miyagawa and

Kurosawa to construct shots using the shading of the trees. In one shot to

highlight the face of the sleeping bandit, all Kurosawa did was to use a mirror

to illuminate Toshiro Mifune’s face using the natural light through the

trees.

The Rashomon Effect (I)

Upon its release and subsequent success, The

film Rashomon created a storytelling trope that is indelibly called “The

Rashomon Effect.” This is the process where a narrative is told

a variety of ways, usually from different character perspectives. The new

retelling reveals more about the story, plot, or its characters. Each perspective,

and its narrator, are ultimately found to be unreliable as the story unfolds

and new information is given. This trope

is often coupled with nonlinear storytelling (Something that Kurosawa also

pioneered) allowing for the maximum level of suspense and shock to be felt by

the audience. By not telling your story from beginning to end, adds to the

feelings of discombobulation that is already set by the erroneous recounting of

events. With this combination, the

audience can not only distrust the characters, but also be suspect as to where

that inaccuracy exists in the timeline of the story itself. Many

films since have used this combination of narrative devices to enhance their

storytelling, ultimately cultivating, and later solidifying Kurosawa’s

legendary auteur status.

SOCIAL ANALYSIS

Rashomon holds

within it classical themes of knowledge production, the basics of criminology, and

a familiar western depiction of masculinity that is, if not pro rape, certainly

complicit in its practice. Upon closer examination, through a sociological

lens, the unreliability of each narration is not only understandable, it’s expected.

The

Rashomon Effect (II)

Christian Davenport

(2010) discusses how the film structure of Kurosawa’s Rashomon leads to “The

Rashomon Effect” in the disciplines of Psychology and Criminology. Davenport (2010) defines “The Rashomon Effect”

as the term describing the unreliability of eyewitness accounts and or

testimony when used as a accurate depiction of events. In an Australian Supreme Court case, it was

determined that individuals and groups tend to have a subjective interpretation

of events that are often, intentionally, or not, motivated by self-interest.[2] In the film, Kurosawa rationalizes

the unreliable narrator by giving the characters a variety of motivations, whether

that be honor, reputation, chastity, or retention of masculinity. All of which alter our perception and

question the legitimacy and accuracy of events. This has been a part of the curriculum

of many criminology courses in debunking the effectiveness of eyewitness

testimony as an accurate depiction of events. Legally, this is hearsay and is

refutable without corroborating evidence (Anderson 2016). The Rashomon effect

is also suspect because of the way that knowledge is produced.

The Sociology of

Knowledge

The Sociology of Knowledge which is interested in the processes in which

Knowledge “is developed, transmitted and maintained in social situations” creates

a distinct reality for particular

individuals (Berger and Luckmann 1966:3).

What all of this means is that knowledge is organic (conditional based

on context); living, as people live. Even what we know and don’t know is even

subject to the right biological and chemical processes in our brains, that

change slow or stop, based upon age and vitality. Knowledge is a perception, and it is

conditional, but that doesn’t make it any less powerful, or important.

Basic Tenets (Seidman 2004: 82-85)

1) Everyday life is fluid, a negotiated

achievement by individuals through social interactions

2) Through interactions, individuals create

social worlds (“universes”) by use of language and adherence to a socially

agreed upon set of symbols; thereby developing solidarity among people.

3) That Social world constructs institutions that

fulfills needs and provides a setting for the development of routines and

behavioral patterns- which is often used to legitimate the social order, (The

Criminal Justice System) Knowledge production (Education) and pacify the

populace (Media, Religion).

4) The individual is then alienated and

repressed, and controlled when the constructed, is understood as natural. This

is usually completed through the generational social learning process of

socialization. E.g. Digital Natives vs

Digital Immigrants, Generational social mobility for whites

5) Through this internalization, the social

worlds that we create constantly try to dominate us. i.e. Frankenstein’s Monster Ex:

Bureaucracy, Capitalism, Militarization, Globalization, and Social Media. It

often succeeds because by this point, we feel too small and insignificant to

tackle such a problem. We believe it is beyond us.

Conceptual Path Model

![]() +/- +/-

+/- +/-

![]() Society

as an Objective Socialization: Society as an Subjective

Society

as an Objective Socialization: Society as an Subjective

Reality is legitimated through The Process of Reality is legitimated

Systemization Social

Learning Through

Personal

Identity

While there are many theories on how

knowledge is produced, the type of knowledge production that explains the

events of Kurosawa’s Rashomon is the process of knowledge production supported

by Michel Foucault.

For Foucault, power lies in social

relationships. Power is a social construction based upon the interactions that

we have with others. Knowledge is then a

biproduct of the power achieved through those interactions. This means that our knowledge and the

“Truths” that we hold on to, matter less than the reproduction of power within

relationships. According to Strathern

(2000)[3],

Foucault believed that knowledge was allowed to contain flaws, gaps, and

contradictions so long as the interaction satisfied the power requirement.

Schirato et al. (2012)[4] states that Foucault

believed that authority and position of power determine the type of knowledge

that is important. For example: being able to categorize and evaluate practices

from an authoritative position (in this case from the legal magistrate

listening to the stories) results in a form of “expert” knowledge being

produced. This knowledge validates the

power relationship and becomes foundational to the general knowledge of a

particular discipline or field, or in this case, the power of the Daimyo.

The Samurai’s Wife, Rape Culture and

Masculine Domination

Since its inception, the

“Rashomon Effect” in its use to maintain the self interest of the speaker, has

been complicated by the simultaneous use of gaslighting and “dog whistling;

especially in cases of contradictory eyewitness statements between a cis-gendered

man and woman, [5]when

recounting the events of a sexual assault.

Like in many actual assaults, the film’s male perpetrator presents the

events as consensual to maintain a positive sense of self.

The

use of The Rashomon effect in this way, and how it consistently dovetails into the

gaslighting of all women, predicates the film itself; when the woodcutter, priest,

and peasant all discount the depiction of events provided by the Samurai’s

wife. They all consistently berate her testimony as “untrustworthy” and excuse

it while also victim blaming her. Bourdieu (1998) mentions that “female being, [is]

being perceived.” Specifically, this happens in the way that the female habitus

(habitual behavior) is a product of other people’s perceptions. Therefore, women’s

subjective representation of themselves, and events they are a party to, is

built from the internalization of experiences and interactions with others.

Now, this is partly just Cooley’s “Looking Glass self” which everyone is affected

by regardless of gender identity. However, because one of the main tenets of

gender socialization is girls and women being taught that their worth is tied

to their relationships with other people (much more so than men), the public

status and perception of women is not based on women themselves, but in the

cultivation and maintenance of relationships they have with other people in their

orbit. This is a form of symbolic violence

that causes women to acquiesce to the patriarchy and overall Masculine Domination.

The Samurai’s wife is not judged by her actions, but by the perception of

her motivations by other men; most who did not witness the event. This also becomes metatextual when considering

that the depictions of the Samurai’s wife that show her at her most unhinged,

is in the events as they are recounted by the other two men. This is gaslighting,

a tactic that is commonly used by men attempting to deflect allegations of rape

and sexual violence, by discrediting women through challenging their mental and

emotional state.

The Bandit and The Samurai, Chase Masculinity

Deflection,

rationalization, and denial of rape and sexual violence is a common mechanism of

self-preservation among male perpetrators. This is part of the cycle of toxic

masculinity that informs their understanding of their (usually) cis gendered

selves. They are locked into “chasing masculinity” as a form of validation. Cis men have to “chase Masculinity due to its inherit

fragility. Masculinity is something that is neither concrete or reinforced,

therefore it needs to be reproduced and achieved in every situation (Walker

2020). Conversely, this also means that a variety of culturally specific

behaviors can also strip someone of their masculinity. In Rashomon, it

is the intersections of Masculinity and the Samurai Class norms that are required

to be satisfied, which leads to the bandit and the Samurai’s stories becoming

suspect.

Cross culturally,

infidelity has always carried with it a double standard stigma split along

gendered lines. Men are often assumed and, in some cases, expected to be

unfaithful to their partner. Meanwhile, women’s infidelity is seen as abhorrent,

and are therefore more likely to be punished for their perceived transgressions

than men. This unequal dichotomy is present in the narrative of Rashomon

when both the bandit and the Samurai reject the Samurai’s wife. First, the rape of his wife does not cause

any kind of compassion in the Samurai. He only sees his wife as an extension of

his own pride and desires (Walker 2020). Thus, after the assault, the Samurai sees

his wife as sullied, and therefore disposable. Similarly, the bandit, upon

hearing the Samurai’s wife’s desire to leave and kill her husband, offers to

murder her for the Samurai’s sake.

According to Alicia Walker

(2020) the fragility of masculinity inevitably causes men to see women as the

mechanism by which they can achieve their masculinity; that even the

satisfaction of female desires and pleasure, eventually does not end up being

about women at all. Rather, it becomes a tool for validating masculinity by praising

men for their commitment to female pleasure.

Similarly, Rashomon’s duel between the Bandit and the Samurai is

couched in the protection or avenging of the “woman’s” honor, when it is just

about saving masculine reputations. This is elucidated when both men recount

their duel. The length and complexity of the duel is directly proportional to

the elevated sense of masculinity they each want to convey/display. The bandit

boasts that the Samurai clashed swords with him 15 times, which he casually admits

is the highest number of exchanges he has experienced in a duel before victory.

Correspondingly, the Samurai’s tale is equally favorable to the bandit’s sword

skills. As one of Walker’s (2020) respondents put it: “Men need their egos

pumped up regularly. We are fragile creatures under all the bravado. (pp71-72).

While this ego pumping is often expected to be exclusively done by men’s (assumed)

female partner, male friendships often act in the same way. Men simultaneously attempt

to expose the fragile masculinity of their peers, while also using women to strength

their perception of masculinity among their male friends (Sanday 2007).

CONCLUSION

Rashomon is

an important touchtone. It is the film that introduced Kurosawa to

international audiences and was so revolutionary in the way the film was shot,

edited, acted, and presented, that it set the cinematic zeitgeist for

generations to come. While the film is

both existential, and critically asks questions about how we process

information and knowledge, going so far as to be used as a shorthand for the inconclusiveness

of eyewitness accounts, it also perpetuates cultural norms regarding gender,

sexual violence, and infidelity that are all too common, regardless of a person’s

country of origin. This is one of Kurosawa’s shortest films, and in that tight

run time he gives the audience a lot to contemplate. While not my favorite

Kurosawa film, it remains an important work in his filmography, and within the

chambara genre itself.

REFERENCES

Anderson, Robert

(2016). "The Rashomon Effect and Communication". Canadian Journal of

Communication. 41 (2): 250–265. doi:10.22230/cjc.2016v41n2a3068. ISSN 0705-3657

Berger, Peter and

Thomas Luckmann. (1966). The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in

the Sociology of Knowledge New York: Anchor Books

Bourdieu, Pierre (1998).

Masculine Domination Stanford, CT Stanford University Press.

Davenport, Christian (2010). "Rashomon

Effect, Observation, and Data Generation". Media Bias, Perspective, and

State Repression: The Black Panther Party. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press. pp. 52–73, esp. 55. ISBN 9780521759700.

Davidson, James F.

(1987) "Memory of Defeat in Japan: A Reappraisal of Rashomon" in

Richie, Donald (ed.). New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, pp. 159–166.

Hashimoto, Akiko

(2015). The Long Defeat: Cultural Trauma, Memory, and Identity in Japan.

New York: Oxford University Press.

Prince, Stephen

(2012). “The Rashomon Effect” in The Current New York: The Criterion

Collection Retrieved on June 15 2021. Retrieved at: https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/195-the-rashomon-effect

Sanday, Peggy

Reeves (2007). Fraternity Gang Rape New York: New York University Press.

Schirato, Tony,

Geoff Danaher, and Jen Webb (2012). Understanding Foucault: A Critical Introduction

2nd. Ed Thousand Oaks: Sage Publishing

Seidman, Steven (2004).

Contested Knowledge: Social Theory Today Malden Blackwell Publishing

Strathern, Paul (2000)

Foucault in 90 Minutes Chicago: Ivan R. Dee.

Walker, Alicia M.

(2020). Chasing Masculinity: Men Validation and Infidelity Cham:

Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan

[1] I discuss this in my previous essay on The

Sociology of Akira

[2]

There is an irony here that in the United States we have the 5th

amendment against self-incrimination in addition to the Rashomon Effect operating

in such a way.

[3] Foucault in 90 Minutes by Paul Strathern

[4] Understanding Foucault: a Critical

Introduction

[5]

This is also constant between a dominant and marginalized group