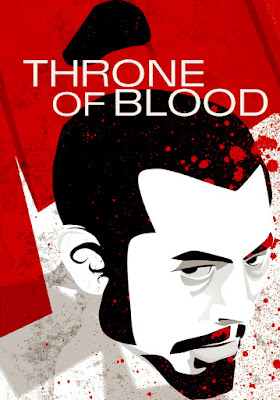

The third film in my analysis of the chambara films of Akira Kurosawa, is the “positively Shakespearean Throne of Blood. An adaptation of Shakespeare’s tragedy, Macbeth, about hubristic intentions, ambitions for power, and madness, Throne of Blood contextualizes these ideas through the prism of late 15th century Japan. Kurosawa masterfully weaves a jidaigeki (period film) with Noh theater creating an amalgamated Masterpiece of adaptation, isolating the themes of power, fragile masculinity and the patriarchal bargain, as well as the dangers of selfish individualism in a collectivist culture. Kurosawa takes Throne of Blood beyond just a derivate, to give an experience that is wholly unique.

PLOT

After a successful victory

over their Daimyo’s enemies, Generals Washizu (Toshiro Mifune) and Miki (Minoru

Chiaki) find themselves lost as they travel to “Spider’s Web Castle”. Upon the road,

they happen upon a Spirit who tells them their fate. Washizu will be the next Daimyo

and Miki’s children will be the first in a long line of feudal era Lords. Each takes no stock in this ethereal

prognostication until the Daimyo satisfies the first of the phantom’s predictions. This confirmation plants seeds of ambition

and desire that ultimately leads to a bloody violent conclusion and

confirmation of the specter’s foreshadowing.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

As

stated previously in other

essays in this series, Kurosawa is infamous for his western

influences. For his literary influences, while Shakespeare takes a close second

to Dostoevsky, Macbeth is the first of of three Shakespeare plays

Kurosawa adapted (The

Bad sleep Well/Hamlet, and

Ran/King

Lear). Throne of Blood is

not a typical shot for shot remake of the classic play. Instead, Kurosawa also

pulls from Noh, a classical form of dance-drama theater cultivated in period Kurosawa

wanted to depict, the 1400’s, to fuse theater and cinema (Prince 2014).

Blending dance, song, poetry and mime with bare sets, and stylized performances

which provided paradoxically powerful movements of its principal cast, the

inclusion of Noh allowed the film to develop a coldness that is often absent of

previous (and future) adaptations (Prince 2014).

Kurosawa’s

“Macbeth” is an amalgamation of western and eastern influences, giving us a

different cultural way of seeing this classic story. Due to its Nohist inspirations: the emptiness

of space, and the inky black, white and grey pallet of how it is shot, gives

the film a unique calligraphical quality that hasn’t been repeated (until

recently). By tying in Buddhist principles to a very western

structure, Kurosawa produces the same story of betrayal, power, and violence without

the source materials reassuring conclusion (Prince 2014). Rather, in Kurosawa’s

tale, the cycle of human violence never ends.

Production

Kurosawa’s original

desire to adapt Macbeth first came to him after the release of Rashomon.

However,

after learning about Orson Wells’ adaptation released in 1948, he decided to

move on to Seven

Samurai and later Ikiru. He eventually circled back to Throne of

Blood when he believed enough time had passed from Wells’ film. Kurosawa

was not originally slated to direct Throne of Blood, but when the budget

ballooned in pre-production, the only way that Toho believed they could recoup

the costs and eventually make a profit, is if the film was directed by Kurosawa.

Shot on sound stages and

two specific locations, Kurosawa constructed the exterior of the castle on Mt

Fuji for its black volcanic soil, which would add to the stark color pallet he was

trying to construct. This decision proved difficult, as they then had to bring

in truck loads of Fuji volcanic soil to the Toho soundstage (where the scenes

in the interior of the Castle were being shot) so that it would match the

exterior shots. This back and forth up and down the mountain proved both

economically and emotionally taxing for Kurosawa and his crew, eventually

seeking aid from an entire battalion (typically 300-1000 soldiers) of US Marines

for transportation and the building of sets.

Yet, the most interesting

and radical aspect of production came narratively during the films climax. When

Washizu attempts in vain to rally his soldiers to go out and fight the coming

onslaught from Noriyasu’s forces, rather than listen

and follow the orders of their commander, the army, previously established as

having a penchant for overwhelming their enemies with a hail of arrows, begin

to loose them upon their Lord. This sequence was shot with real arrows while

star Toshiro Mifune was in frame. Instead of achieving this through special

effects, trained archers were used; creatin a choreography between them and

Mifune, involving Mifune waving his hands during the sequence to indicate the direction

he was moving to the archers off screen.

Every arrow hit was real, (except for the shot through the neck) taken

by Mifune who wore wooden blocks of protection under his costume. Some of the

closer arrow shots were hollowed out and launched on wires for added safety. This

process resulted in Mifune showing real fear during the sequence which added to

the gravity of the climax and the overall legacy of the film.

SOCIAL ANALYSIS

A

lot has been written and analyzed about Macbeth and its many adaptations.

The themes of greed, hubris, and ascending the ladders of power have been tilled

over for centuries. Yet, the elements

that Kurosawa uses to demonize individualism through his changes to

Shakespeare’s original story, the mechanisms of power, and the expressions of

fragile masculinity and the patriarchal bargain, are Sociologically interesting

and valuable to explore.

Individualism

vs. Collectivism

What makes Kurosawa’s adaptation of Macbeth

interesting

and popular, regardless of the narrative changes and

liberties, is the criticism of individualism in favor of a collectivist mindset.

Individualism, prominent in Western cultures, support egocentric ambition and

grasps at money and power. Your ability to succeed is not based in any sort of

loyalty to a collective or other group, but in your own cunning, ingenuity, and

uniqueness. Thus, focusing on the rights of the individual as opposed to the

group. Collectivism, common in Eastern cultures,

sees value in the social group and group formation as valuable and important to

the overall function of society. The changes

made by Kurosawa to Macbeth in Throne of Blood, highlights this

difference and places individualism, not the theatrical tragic flaw of hubris (commonly

the downfall of Sir and Lady Macbeth in the play), as the catalyst for the

demise of its central characters.

The replacement

of the thematic catalyst of hubris for Individualism in Throne of Blood

happens through minimal narrative changes. Firstly, Asaji becomes pregnant (unlike

Lady Macbeth) which motivates Washizu to furthering the plans to kill Miki.

This then allows for greater context for Asaji’s mental breakdown motivated by

the birth of a stillborn child, rather than just guilt and paranoia. Once

Washizu becomes Daimyo at the beginning of the film, he clearly states that he

has no intention of any further malevolent machinations. He is resigned and

almost happy to both have his position, and then give that position up to

Miki’s heir. Yet, it is the temptation of his own dynasty that motivates his

later actions in the film. Secondly, the death of Washizu is not from single

combat with Noriyasu (the Macduff proxy) as it is in the play. In its place,

Washizu dies by being felled by arrows from his own troops. In that last

action, Kurosawa highlights Washizu’s individualistic ambitions to retain power

as madness; one that needs to be eliminated by the collective action of his

people. This anti-individualism is reinforced by the chorus at the end of the

film, indicating to the audience that Washizu’s soul never made it to the

afterlife. His soul remained on earth in eternal purgatory, and thus is

presented as a cautionary tale of western individualism.

Fragile

Masculinity and The Patriarchal Bargain

One

of the powerful mechanisms of socialization (social learning) in any society is

gender socialization. The process by which individuals learn what it means, and

how to perform the gender identities that are considered acceptable within their

society. These messages are then reinforced by various social institutions for

the purposes of governance and social control. Typically, in western

Patriarchal (male centered) societies: the values, ideals, and behaviors

associated with masculinity and maleness are exalted, encouraged, and

normalized; made both invisible and hegemonic.

Yet, because masculinity is valued and expected (especially among men), this

minimizes the way that identified boys and men can express themselves. Because

these masculine standards are so rigid, they can only perform (a narrow form of)

masculinity without sanction. Thus, any social situation identified boys and

men find themselves in (especially cis gendered men) they may be called upon to

validate their masculinity. This also means that every social situation, is

another chance their masculine performance will be interrogated and revoked.

The revocation and reinstatement of individuals’ masculinity is a cycle of cis gendered

social control that makes masculinity itself fragile.

According to Bourdieu (1998) “the social order

functions as an intense symbolic machine tending to ratify the masculine

domination on which it was founded.”(p 9).

Thus, men need to be men, or they are sanctioned until they reclaim

their masculinity in ways that reinforce the narrowly defined and dangerous

forms of masculinity accepted by the Patriarchy (usually using sex or violence

to achieve it). It is not just cishet men that police other men in this system.

Cis gendered women are also socialized to critique men’s performance of masculinity;

the result of which is immediate emasculation. It is this masculine sanctioning

that Asaji uses against Washizu in Throne of Blood when she questions

his resolve to their agreed upon actions (and therefore his masculinity).

Mifune’s long vacant stares indicate the depth of her evisceration of his fragile

masculinity with such a simple look. Washizu is then pressured to salvage his

masculinity through the added violence against Miki and his sons.

Women, socialized into a

misogynistic and patriarchal culture are given value in their bodies, and in

their relationships (especially with cishet men). Thus, cishet women are often

taught to find value in themselves in this system through their relationships

with other people, rather than believing they have value outright. Not only

does this reinforce the norm of women performing a lot of emotional labor for all

their male relationships (sons, husbands, fathers etc.); this also encourages

the patriarchal bargain. The patriarchal

bargain is the different strategies employed by women in a patriarchal system

to maximize security and optimize life options with varying potential for

active or passive resistance in the face of oppression (Kandiyoti 1988). Given that Throne of Blood is set in

the 1400’s, in a masculine emphasized caste system, the patriarchal bargain is

presented as one of the only legitimate avenues for women to gain status and

power. Asaji motivates and berates her husband into violence to seize power for

herself through him. Her ruthlessness (overtly gendered male in Feudal Japan)

is hidden behind a façade of diminutive femininity, manipulating her husband

through social and symbolic castration to be able to access the power that is

denied her through a gendered social system.

Power and its lure

The Weberian definition

of power is the ability to realize your will even when others resist (Weber 1978).

This presupposes that a person has already acquired said power (in whatever

material or symbolic form it takes). To acquire power, you need to understand

where power resides, and while there are many forms of power that exist, the masculine

misogynistic domination of the patriarchal rule that resides in the institutional

system seems to take precedence in Throne of Blood.

Power is usually

generated by those who are in

positions of high authority in powerful social institutions (usually men) who set

the value of the different forms of capital (Financial, cultural, and Symbolic)[1],

and as such, have an undue advantage in the struggles for power within a

particular field[2]. The habitus (habitual behaviors/norms) that

is affected by those types of capital is a form of bio power[3]

that “The Power Elite” (again usually men) has over the rest of the structure,

especially those within the “mass society” (the everyday public outside positions

of power). Therefore, the ignorance and

apathy of “the mass society” is the product of the inability to acquire

multiple forms of capital and habitual behaviors even if they are potentially

able to access it through the symbolic capital. (Mills 2000, Foucault 1977,

hooks 2000, Bourdieu, 1987). This raises a couple of important and seemingly

opposite points:

1.

Symbolic Capital-

abstract forms of privilege based upon a variety of intersecting identities

(race, gender expression, sexuality, disability) does not guarantee access to,

nor exercise of other forms of power, while also not acting as a barrier to

that power (as it does for marginalized identities)

2.

Symbolic

Capital does make the acquisition of other forms of power easier through Symbolic

Power: the ability to impose meanings upon others as “normal” or “natural”

without seeming coercive. This happens when a power system sets cishet able-bodied

white men as the default. This makes the symbolic power invisible to those that

have it, transforming expectation into entitlement

In Throne

of Blood, both Washizu and Miki are introduced as “Men of Power” through their

Military prowess and command over their armies. At the outset of the film, both

understand their power and where it comes from. (Mills 2008). However, after their

encounter with the Spirit in Spider’s Web Forrest, and the fulfillment of its

first proclamation, for Washizu, this privilege becomes invisible. Then, as the

story progresses, his ambition to amass power becomes an expectation. As the

bodies begin to pile, and the blood continues to flow, that expectation is rationalized

into entitlement to explain the violent murders he either performs or condones;

using the words of the spirit as evidence.

This is the demagoguery of masculinity, one that needs to be dismantled.

According to de Beauvior

(2011):

Indeed, [man] is a child , a contingent and vulnerable body, an

innocent, an unwanted drone, a mean tyrant, an egotist, a vain man: and he is

also a liberating hero, the divinity who sets the standards. His desire is a

gross appetite, his embrace a degrading chore: yet his ardor and virile force

are also a demiurgic energy…that woman confined to immanence tries to keep man

in this prison as well; thus the prison will merge with the world and she will

no longer suffer from being shut up in it: the mother, the wife, the lover are

all jailers; society codified by men decrees that women is inferior: she can

only abolish this inferiority by destroying male superiority (p 655, 754)

Given Beauvior’s point, this could be an interesting motivation for Lady Macbeth to manipulate her husband into the killing of Duncan in other (future) adaptations of Macbeth, that I have yet to see.

CONCLUSION

Throne of Blood is a

Masterpiece and is heralded as one of the greatest Shakespeare adaptations in history.

Even without the romanticized dialogue, typically retained in most adaptations,

Kurosawa invokes the classic emotions of the play in a Japanese cultural

context. It’s recontextualization of the Scottish story into Feudal Japan

speaks to the universality of desire, greed and cunning within a militarized patriarchal

system. One that endlessly rewards violence and deception with more of the same. Yet, regardless of its organization as a

cautionary tale, that does not guarantee the public perception and consumption of

it will see it as such.

REFERENCES

Bourdieu Pierre 1987. Distinction: A Social

Critique of the Judgement of Taste Massachusetts: Harvard University Press

_____________ 1998. Masculine

Domination. Stanford: Standford University Press

de Beauvior Simone 2011. The Second Sex New

York: Vintage Books

Foucault Michel 1977. Discipline and Punish:

The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books

hooks bell 2000. Feminist Theory: From Margin

to Center 2nd edition Massachusetts:

South End Press

Kandiyoti, Deniz. 1988. “Bargaining

with Patriarchy.” In Gender and Society

2, no. 3 pp 274–90. Retrieved on 1/3/22 Retrieved at http://www.jstor.org/stable/190357

Mills, C. Wright 2000. The Power Elite New

York: Oxford University Press

______________2008 “On

Knowledge and Power” Pp. 125-137 in The Politics of Truth: Selected Writings

of C. Wright Mills New York

Prince, Stephen 2014.

“Shakespeare Transposed” in The Current New York: The Criterion

Collection Retrieved on Feb 6 2022. Retrieved at https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/270-throne-of-blood-shakespeare-transposed

Weber Max 1978. Economy

and Society California: University

of California Press.

[1] Economic Capital- wealth (income and

assets)

Cultural Capital

– Education and other forms of knowledge, skills, goods and services

Social Capital- Family,

acquaintances and other Social Networks

Symbolic Capital-

legitimation, Abstract forms of privilege (white, male, hetero, able bodied)

[2] 1) They are arenas of struggle for

control over valued resources (forms of capital) which become social relations

of power.

2) They

are structured spaces of dominant and subordinate positions based upon types

and amounts of capital Usually unequally

distributed

3) The

impose upon actors (individuals) specific forms of struggle they are the space

in which conflict resides

4) Fields

are often structured by their own internal mechanisms of development allowing

them to hold some autonomy