The

twelfth film in my continuing analysis of The

Films of Hayao Miyazaki is the melancholic meditative

masterpiece, The

Boy and the Heron. A blistering elevation of the artform,

Miyazaki’s latest visual tapestry is a generationally expansive collaboration

that is contemplative of death, (social and self) destruction and the human dynasty.

While Miyazaki retreads some narratively foundational elements found in his

other semi-autobiographical work, he comes at the

material from the opposite direction, making the prepubescent protagonist his

personal proxy; even when most critics see the wearily old Uncle as his artistic

alternate. Regardless of the form of his fictional facsimile, Miyazaki’s

current, and perhaps final film, is a thoughtful treatise on the crisis and

value of legacy, from the greatest animation auteur of the 20th

century.

PLOT

In

World War II era Japan, Mahito Maki fails to rescue his mother from a hospital

fire after its bombed by the Allies. Once the War concludes, Mahito and his

father move to the country where his father takes a new wife…Mahito’s aunt (his

mother’s sister). Still grieving the loss of his mother, Mahito is stunned into

virtual silence over these events. But

when a mysterious Heron beckons him into the Underworld to “save his mother.”,

Mahito cannot resist the pull of a (perceived) redemptive adventure. However,

what sets Mahito’s motivations at the beginning of this journey, quickly changes

as the Heron is found to be untrustworthy. Overseen by an enigmatic elderly man,

Mahito ventures deeper into this otherworld that is full of plundering parakeets,

a Firestarter, and soul consuming pelicans. Amidst the journey’s peril, he soon

realizes that the parabolic arc of life is unpredictable; felled by many

difficult and nigh impossible choices.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Considering

that Miyazaki just celebrated his 83rd birthday on Jan 5th,

2024, it is difficult to discuss the historical context of The Boy and the

Heron without also looking at this film as his magnum opus. Granted, given

how many times Miyazaki likes to publicly retire[1], and then recant those

statements, it is likely that Miyazaki will be working on “something” until his

untimely death.[2]

Still, this is most likely his final completed film. Thus, indicative of that,

some retrospective on Ghibli is also required.

Much of the heavy lifting

of that studio reflection was completed by a duology of documentaries: The

Kingdom of Dreams and Madness (2014), cataloging the production of his previous

“last” film: The

Wind Rises, and Never-Ending Man:

Hayao Miyazaki (2018) both of which fail to disentangle Miyazaki from

Ghibli himself, often making them one in the same. It is important to question

then, what is Ghibli without Miyazaki? Serendipitously, Miyazaki answered this

very question, in the first documentary saying: “I know what will happen…It

will end.” In the documentary, this quote is juxtaposed with Miyazaki sitting

on a picnic style park bench outside of Ghibli studios while also admiring a

cat, and looking out at the beauty of the day he is experiencing. There is no

malice, regret, or animosity in that statement. Instead, it has an intimation

of reserved contentment. Miyazaki has never been one to get nostalgically

mournful over the loss of the studio, which shuttered its doors several times in

between Miyazaki’s projects. Even though these periods were eventually labeled

a “hiatus”, at the time of each closure, it was unclear if the studio would

ever continue. The focal point of

Miyazaki’s prideful ambition was always the ability to create and maintain his

artistic vision over the solvency and success of the company. Unfortunately,

when that vision is threatened, as it was during the production of The Boy

and the Heron, Miyazaki’s choices and the direction of the company opened

himself up to claims of hypocrisy.

Production

Miyazaki

has always been a

proponent of the theatrical experience, believing that his, and

all of the Ghibli films should be released and seen in theaters, or exclusively

released on high quality physical media for home viewing in the best possible

format. This pretentious position won him

(and Ghibli) the praise of film geeks, and scholars as one of the last bastions

of cinematic artistry. To be clear, irrespective

of the dramatic discourse surrounding this subject, there is sufficiently

well documented evidence that when you have physical media,

the quality of the video is better (lack of compression and a non-reliance on

Internet speed) and you actually physically own a copy of the film; unlike with

streaming where you only pay for access ( Arditi 2021, 2023).

Additionally,

Miyazaki has never been interested in expanding the Ghibli brand; including merchandising

nor the outright licensing of Ghibli characters to inundate the market for the

purposes of profit. This was what had always separated Ghibli from what some

would call their western equivalent in Disney. Disney was the purveyor of the maximalist

ubiquity of a profit driven monoculture that they themselves control; and

Ghibli was a minimalist, at cost artisan studio that was run more like a

nonprofit; with most of its revenue going back into the company for future

projects. Unfortunately, in this capitalist

system, the Ghibli model was only sustainable if budgets were kept low, and

deadlines were met. The moment that one or both conditions changed, then their artistic

morality would be in danger of being compromised.

Miyazaki first began

working on what would eventually become The Boy and the Heron in 2016

before the film was officially greenlit. A year later, when the project was

announced, the loose description was that it was going to be a adaptation of

the book “How

do you Live?” The only other information given to the

public was a devastating admission of motivation by Miyazaki, stating that the film

was being made for his grandson because: “Grandpa

is going into the next world soon, but he’s leaving behind this film.” And

everyone wept. Beyond these tidbits, little was known about the film for years.

Soon, those close to Miyazaki and others at Ghibli were worried the film was

never going to be finished. This is because, in the intervening years, Miyazaki

was grieving the death of fellow legendary animation director, Isao Takahata

whom he had used as a model for Grand Uncle in his new film, and due to

Miyazaki’s aging, his process was becoming more meticulously slow. Whereas

production on previous Miyazaki films would yield 7-10 minutes of finished film

per month, on The Boy and the Heron, Miyazaki was averaging 1 minute per

month; only completing about 15% of the final film by winter 2019.

The

Odyssean production eventually became so protracted that its budget began to balloon

to the point that it set the record for the

most expensive film Japan has ever created, and threatened

the viability of the studio. Therefore, Miyazaki and famed Ghibli producer and

collaborator, Toshiro Suzuki were at a crossroads. Do they risk not finishing

the film that may very well be Miyazaki’s last? Or, do they reluctantly

open another revenue stream (pun intended) that they were previously

recalcitrant to on morally artistic grounds? Eventually, Suzuki

and Ghibli capitulated to a streaming deal with (then named) HBOMAX and

began the development of a Ghibli theme park in 2017. Both

decisions were fueled by a desire to finish this most recent project.

The drastic

reversal of the HBOMAX deal in 2020 after doubling down on their original position

a scant year prior, caused Miyazaki, Suzuki and Ghibli to be exposed to public

blowback. A company that often prides itself as being principled over profit was

now open to attacks of character, and even greater comparisons to Disney. Yet, in the wake of this decision, none of

that came to pass. Why? Because consumers were gaining greater access to a

thing that they love (and perhaps feel entitled to), profit was being made for Warner

Media (parent company of HBOMAX now just MAX) in the form of new subscribers,

and Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli got money to put back into current and future projects.

Cynically, a common response from many people to the understanding that there

is no ethical consumption under capitalism is that there should be no morality

or ethics in the pursuit of profit.

These are not the same. Understanding

the unethical process of an economic system does not imply a tacit and blanket

support for immoral practices in the accumulation of wealth; especially around

labor (Just look at 2023’s “Hot Labor Summer”). Additionally, recognition of an

individual’s participation in the unethical systems as a necessary requirement

for survival does not absolve them from attempting to minimize the amount or type

of participation in which they engage. By accepting this streaming deal, Ghibli

is not slouching toward (becoming) Disney. Suzuki had to (basically) trick

Miyazaki into agreeing to it and played

on his ignorance in order to succeed. Also, this decision

was not taken lightly as it often is with the nebulous greed of Western

Corporate Executives. It was a decision based on a desire to complete a project

and expand the distribution of already made films. Therefore, the story of how

Ghibli films went to streaming illustrates that when capitalism forces you into

“a Devil’s Bargain” of compromised morality, do so for a benevolent reason

without giving more of yourself than is necessary. With funding secured, the next

step for the production team was to increase the pace of production.

To speed up production,

Miyazaki began to embrace a more traditional animation director role. Suzuki

had convinced him to take on a more supervisory position on the production in its

later stages. To make Miyazaki more comfortable with this transition, Suzuki

brought in former Ghibli animators who themselves have gone on to become well-known

animation directors in Japan. The most

famous was Takashi Honda of Neon Genesis Evangelion and Mobile Suit Gundam

fame, who took over storyboards for some of the film’s major sequences. While

this is common in animation, this approach has also been used in live action. If

an aging director wants to make a film, as a part of the deal, major studios

may require an additional director to be on set in case the director dies or is

incapacitated while filming. Famously, Paul Thomas Anderson was hired to be “a

backup director” for Robert Altman on A Prairie Home Companion, while

Coppola, Lucas and Spielberg, integral to the creation of Akira Kurosawa’s

final two Chambara

Films: Kagemusha

and Ran; gave producers comfort

by also being on set. However, unlike other directors, Miyazaki had the

privilege of former workers coming back to help him finish (what could be) his

final film. This was a chance for many of these animators to give back to the

master on which they cut their teeth. As

Calligrapher Tamio Yoshida once said, “To Surpass the Master, Repays the Debt.”

As of this writing, the

dozenth film in Miyazaki’s oeuvre is the most successful film in Japan and topped

the US box office in its first week of release; making a current total of $149

Million in international and domestic box office receipts. This was after a minimal to nearly nonexistent

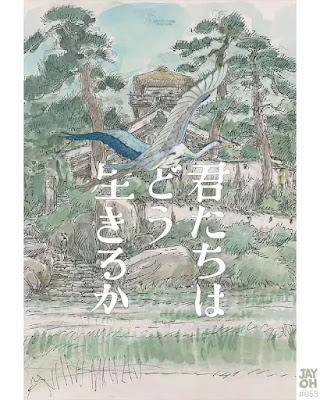

marketing campaign. The reason being that

the cultural capital of Studio Ghibli elevated by the potential of it being

Miyazaki’s last, basically sells the film. Rather than a blitzkrieg of ads, Suzuki

simply released a single vague white poster. On the poster, was a picture of a

Heron drawn in the style of calligraphy with the name of the film above it. He

then took the money he would have spent on marketing and put it back into the

film. This confident strategy even led the sales of the book “How Do I live?”

to increase, as people were searching for clues about the film’s plot by

reading it. This became such

an issue that Suzuki had the make a statement to the press that

the association between the film and the book was minimal. Furthermore, the film has also been making

the festival circuit and picking up pending award nominations, including from

the Annie Awards and BAFTAs; to winning awards outright from Major US regional

Critics associations including New York and Chicago. The film is expected to at

least get nominated for Best Animated Feature at the 2024 Oscars, but also

could be in contention for Best Film, Best Foreign Language Film, Best Director,

and Best Score for longtime collaborator Joe Hisaishi beautiful orchestral melody.

SOCIAL ANALYSIS

As

with many directors, Miyazaki’s work always comes back to a lot of the same central

themes across his filmography, such as: Feminism,

Environmentalism,

Anti-War

massaging, and Work

and Identity. With The Boy and The Heron,

Miyazaki additionally grapples with loss, legacy and Masculinity as if he is retrospectively

contemplating the value of his own existence, his place in culture through this

film.[3]

Loss,

Death, and Grief

The beginning of The

Boy and the Heron, opens like a nightmare. Mahito is awoken by the firebombing

of the hospital where his mother is a patient. The sequence of him running to

help put out the flames is purposefully drawn with few clear lines, blurring

the images of the fire, the crowd, and Mahito, to give the audience the sense

of discombobulated panic someone feels when they experience a trauma inducing

event. This is something that will stick with Mahito. He will internalize these

events as failure, no matter how vain his efforts. During this sequence,

Miyazaki includes a shot of Mahito going back to his house to get “properly”

dressed. This is to emphasize both the banality of tragedy, that even though

your life is falling apart, you still have to put on clothes (or eat, or go to work,

care for children etc.) and the way that those moments stick with you. Mahito

will always wonder, regardless of its rationality or truth, if he had not taken

the extra time to put on his pants, would he have been able to save his mother?

Of course, he couldn’t, but our brains, especially when we are young, tend to

be bullies, convincing us of heroic delusions of grandeur.

The loss of his mother is

the driving motivational force for Mahito throughout the film. The Heron taunts

Mahito using the lure of saving his mother, to get him to follow The Heron into

the Underworld. Even when the ruse is revealed, Mahito elects to find his

Stepmother, herself mysteriously detained, making her into his birth mother’s

proxy. If he can save her, then, in his own eyes, he will be redeemed for not

being able to save his first mother at the hospital. The guilt will be

assuaged. This belief drives Mahito.

Travis Herchi’s (1969)

social bond theory[4]

discusses that the belief in social laws, and the legitimacy of their

enforcement, is an essential mechanism for the continued reproduction of the

current social order. Durkheim (2001) focuses on the importance of religious

belief; stating that belief itself needs people in order to exist.

Additionally, many of us incorrectly identify the source for feelings of

elation and spiritual connection as being located in a higher power, or a

supreme being, whereas it is more likely generated by various social groups.

Durkheim (2001) calls this phenomenon “collective effervescence through

emotional contagion.” This is the process by which individuals within a small

group setting become collectively influenced by the emotions and moods of the

people around them. For some, this collective effervescence makes them feel

better, transforming their dower mood into one that is more delightful. With

others, their mood can be so powerfully negative, that it can act like a virus sapping

the joy from everyone around them. This is the state of Mahito at the beginning

of the film, infecting others with his rage and pain, getting into fights and

inflicting self-harm. Yet, Durkheim (2001) also points out that while belief is

important to maintain/retain the power of religion and motivate people into

social action the way it does Mahito; the content of that belief is rather

moot. It doesn’t matter what you believe, what matters is that you

believe. The faith that is generated is

not merely an individual thing, it is based upon our learning, and the sharing

of experiences within society.

Mahito’s faith is in his

determination to save his mother, believing he can do it himself. Nevertheless,

it is the people around him, and his own family, that support him, build him

up, and help him on his journey that allows him to be successful. Durkheim (2001) says plainly that we create

stories about Gods. We define what is sacred, and build communities around the

things that we believe, and have faith in. It is us, the group, that has power;

not anything beyond that. One of the main functions of religion as a social institution

is that it provides us with answers about mortality (What will happen when we

die?) and morality (How Should We Live?). Rather than these answers

be handed to him, Mahito reads a book, and goes on a spiritual adventure rife

with metaphors about what it is like to live, have generational legacy, and love.

He is far more adult at the end of the film than he is at the beginning; more

ready to live the life in front of him, with a greater sense of purpose and focus.

Subcultures as Cults

Paradoxically, even those

of us that do not hold religious beliefs, nor faith in anything spiritual, tend

to satisfy the same organizational and institutional needs through our

participation in social groups. For some, this might be the group you have a

weekly pick-up basketball game with, or a community theater troupe. But in the

context of Miyazaki, the anime fan subculture is the best example. Many social group subcultures take on and

embody various aspects of religion. They create sacred text and deify

individuals as their gods, they have strict hierarchical rules and opinions

that are designed to be exclusionary and have unique dress codes. All these

aspects of religion are satisfied by the anime fan subculture. Whatever show or

film someone is into, becomes the sacred text, its creator is exalted and

venerated as a paragon, communities validate and invalidate opinions as a way

to justify the inclusion and exclusion of members and non-members to their

group (Think about the “Umm actually…” section of fandoms) and cosplaying becomes

the unique dress code. The anime fan subculture has religious overtones, but

because it does not have access to power to legitimate its identity within the

already establish social structure; they operate more like a cult…as all

fandoms do. The irony of this is when faced with his own deification and the

religious devotion with which both fans and animator prostrate at his feet,

Miyazaki rejected them; iconically stating that “Anime was a mistake. It’s

nothing but Trash.” What do we mere mortals do when our manufactured gods

reject us so completely?

The Precarity of Birth

and Death: WaraWara and the Pelicans

Weber (1956) defines

spirits as “neither soul, demon or god, but something indeterminate, material

yet invisible, nonpersonal and yet somehow endowed with volition.” (3) Western

cultures tend to apply and imbue that sense of volition from an individual

perspective. Western religions believe that an individual soul is a unique

personality that exists prior to any kind of social molding through the society

that they are born into. Contradictorily, Eastern cultures often see this sense

of volition as connected to groups and individuals before them. There is a

greater valuation of ancestry among Eastern cultures that typically manifests

itself through the concept of filial piety. This is the idea that individual

actions reflect on the entire family; currently, and throughout generations.

Therefore, shame and glory are very much a collectivist concept in Eastern

societies rather than an individual one. These juxtaposed ideas of spirits are

embodied in the film by the entanglement of the WaraWara, and the Pelicans.

As Mahito enters the

spirit world he encounters a younger version of one of his old maids, Kiriko.

She tells him that most of the people in this place are dead; except for the

WaraWara, primordial souls that are floating to the real world to be born. As

the ritual commences and the WaraWara begin to ascend into their “birth” in the

real world, a flock of pelicans swoop in and begins to devour the WaraWara

whole. Mahito, Kiriko and Lady Hemi succeed in igniting the pelicans and

driving the rest away. Later, when confronting one of the pelicans that are

dying, Mahito asks why they were eating souls of those yet to be (re)born? The

pelican simply stated that they were brought there by The Creator for that very

purpose. Since Mahito’s raging against death and therefore fixated on the

saving/reviving of his mother in this moment, he does not understand the

inextricable link between life and death that the WaraWara and the pelicans

represent.

The symbiosis of the

WaraWara and the Pelicans moves beyond just a simple understanding of an

environmental sense of “balance” The circle of life. Miyazaki leaves the ritual

vague enough that for it to be used as a narrative allegory for a variety of

social issues such as overpopulation, birth control, and the systemization of

bureaucratized death.

If the tiny chibi-like WaraWara are souls in

the spirit world, waiting to be (re)born, the pelicans are necessary to curb

the very real threat to overpopulation. Ostensibly, the pelicans act as a

literal form of birth control…controlling new souls from being born into the

real world for the purpose of resource management. What Mahito fails to see

until his actual conversation with a pelican is that they are a part of an

integrated system attempts to organize the process of life, death, and

rebirth. Consider the bureaucracy of

death, the mechanisms, processes, and profit that is made off death. From

granting the job security of coroners, to grief counselors and morticians,

death is a lucrative business (everyone dies, so there always a demand for jobs

that eliminate the endless surplus of the dead). It is the order and

monetization of the end of life. In Miyazaki’s world, the pelicans are just janitors.

As

indicated in previous films, Miyazaki is also acutely aware of the earth’s

finite resources, and the earth’s ability to sustain a certain amount of people

before its depletion and eventual destruction. Yet, consistently, our

enculturated and internalized desires for children rarely consider the

environment. This is because the cultural value of the next generation is based

on ideals of personal and familial legacy and not the longevity of the planet.

For many, regardless of culture or context, having children is the quickest and

easiest way to achieve validation and a sense of purpose; the satisfaction of

which supersedes our valuation of earth’s sustainability. Additionally, because

we do not have equal distribution of agricultural assets, wealthy and more

powerful countries obtain and consume more than their fair share of resources. The

United States only accounts for less than 5% of Global population but consumes

20-30% of all global resources while producing 50% of all global waste. Therefore, the wealth and status of a country

also determines their level of unequal distribution of resources, which in turn

creates a culture around that amount of resource consumption cultivating

a since of entitlement to that level of access. Cultural norms, rituals and

interactions are based around this pattern of unsustainable practices, thereby

making overconsumption seem necessary. Under these conditions, wealthier,

environmentally rich countries (rich in access, not geography) have an easier

life than those that don’t, in part because of their higher resource

consumption, and because their wealth shields them from the effects of

environmental destruction/depletion better than poorer (usually non-white)

countries.

Masculinity and a Sense of Colonialism

The correlation

between masculinity and capitalism has been well documented. Historically, in

many western societies this relationship is interdependent. The extent to which

men can achieve and amass power is directly caused by the expansion of

capitalism. Similarly, economic power is then perceived as a masculine trait causing

sexist laws, rules, and regulations to be enacted, ultimately defining capitalist

economic success as being exclusively achievable by men. The perfect progeny of

this unholy union is colonialism.

Colonialism

can be defined as the process by which an indigenous people are conquered

(usually by a foreign invading force) followed by the creation of an

organization controlled by members of the conquering polity and the

establishment of rule over the conquered territory and population (Steinmetz

2014).[5] Colonialism is the

cancerous consumptive crawl of capitalism coupled with the aggressive menagerie

of masculinity with a serving of white supremacy.

The interlocking

mechanisms of race, class and gender that make colonialism possible also allow

it to be polymorphic. The force of colonialism was at first the force of violence,

when that was met with resistance, the process pivoted, reinvented itself to

lean heavier on its capitalist roots and its implication of progress. As

colonialism masks itself as advanced technology, many native societies do not

see how culture comes with it. Therefore, the resulting cultural diffusion

through the process of global trade, and the expansion of the global economy is

not equal. Instead, this is a subtle form of cultural imperialism.

Mary Fraser (2023), like

George Romero before her, analogizes white male colonialist global capitalism as

being cannibalistic. Capitalism is an ouroboros, people can not generate enough

through paid work to support themselves and under capitalism everyone is a

resource that gets used. When societies historically restrict access to

economic participation due to sexist racist and ableist bigotry, the eventual

granting of that access can seem like liberation for a time…because participation

in capitalism is a necessity for survival. But that access, framed as liberty,

masks the ritualized objectification of being economically oppressed. Therefore,

part of the fight for justice, whether for racial, gender, sexual, or disabled freedom

is fighting for their right to be exploited under capitalism. This is not the

type of hegemony that fosters revolution, it is the type of hegemony that eventually

leads to the erosion of facts, science, reason, and civility as what befalls The

Parakeet King and his Monarchy in the film.

Late in the film,

Mahito’s search for his aunt/stepmom leads him to uncover an underground

society of Parakeets. Like the Pelican’s, they were originally brought to this

world by his Grand Uncle, The Creator, as a patch work solution to avert a

potential catastrophe. Since then, the Parakeets have developed into humanoid

forms, created a structured dictatorial political and social order, and gained

a penchant for the taste of human flesh, attempting to eat Mahito and Lady Hemi

when they encountered them. It is also

the actions of The Parakeet King, his inept staking of the blocks, that

ultimately causes The Creator’s world to crumble.

The hubris of The

Parakeet King can be allegorical to Western Societies relationship with God. History

has given us a plethora of examples of politically powerful men playing God.

Whether that be the judgement and execution of life and death sentences, the

more mundane erection of city skylines, cathedrals, and

statues, to the more complicated manufactured imbroglio between religion and

capitalism, all point to a desired deification of humanity…(mostly) by and for

men. Similarly, The Parakeet King exhibits many masculine traits, chief among

them being self-determination to the point of an over-inflated sense of

self-importance. This is coupled with a willingness to use violence as a

mechanism of validation that becomes inevitably virulent; dooming the world to

justify their own existence.

The Parakeet King is only Miyazaki’s latest character to be a cautionary tale for the dangers of white masculine capitalist colonialism. From the Count of Cagliostro to No Face in the Bathhouse, Miyazaki has always been critical of capitalism. Most of his characters that support capitalism either are destroyed, disillusioned or die, while his protagonists embrace the hospitality of socialism and emotional growth. The glaringly obvious exception to this statement is Kiki, of Kiki’s Delivery Service, who is both an entrepreneur (saw a hole in the market that she could fill) and a small business owner. However, her predilection for profit mirrors that of Miyazaki and Ghibli themselves. For Kiki, profit is not an ethos, it is the means of subsistence and a mechanism for creative expression.

Legacy

The enmity we have with

death correlates with our enculturated validation of masculinity and the

development of patriarchy to heavily weight the importance of legacy. Our

valuing of self-worth primarily through the prism of longevity, ostensibly

seeking immortality, has placed an overabundant focus on reproduction. For

many, sex and reproduction are the cheapest and easiest way to impact the world

through your genealogy. We have used the

creation of children to get laws passed, encapsulate ideas about gender, and to

maintain social control; all through subtle or direct threats to personal

legacy.

In this context, The

Boy and the Heron forces us to grapple with the passing of generations,

what is accepted, what is left behind, and what is changed. In the

conversations between Mahito and his Grand Uncle, Miyazaki challenges the

audience to reconcile our culturally incongruous ideas about legacy by posing

two questions: What is the responsibility one generation has to the next? and What

happens when the next generation is resentful and does not want to continue the

previous generation’s work, allowing it to die?

The first question and conversation reveal,

much like the context suggests above, that the existence of new or next

generations are not about them at all; instead, it is about the people they are

born to. New generations are a motivating force for life and society to exist.

They maintain the social order by providing personal investment and stakes in their

parent’s generation that needs a reason to keep living and working regardless

of its diminished sense of fulfilment.

The second question and conversation

deconstruct the social and cultural “guard rails” that our society employs to

maintain the status quo. One of the

fundamental generational “guard rails” is the process of socialization; the

social learning of rules, regulations, norms, and values of our society from

one generation to another. Embedded in these rules, regulations, norms, and

values are generational messages about culture that, much like the children

themselves, get reproduced. This not

only is a maintenance of the social order, but a solidification of generational

legacy. This normalization manifests itself in the form of logical fallacies

(“That’s How it’s always been done.”) and results in an inherited earth that is

on the brink of collapse (climate change, War, Genocide, and crumbling social

Institutions). Therefore, it is obvious

that the children of today’s adults would be resentful because of the generational

debt they are being saddled with. However, even as Mahito rejects his Grand

Uncle’s pleas, leaving the world that was created to be demolished, as Mahito leaves,

he still picks up some of the pieces to build something himself. In this,

Miyazaki illustrates that even if there is a generational blight through the

rejection of norms, the next generation is still going to have to build

something out of the rubble.

CONCLUSION

The

Boy and the Heron is a masterpiece. While this descriptor is

both common and apt when writing about any Miyazaki film, the way this film

encapsulates, themes, art styles, character tropes of his other previous films,

as well as amalgamating the legacy of Ghibli animators by having former

employees come back to help finish the project, this film is the perfect

representation of Miyazaki and a distillation of his impact on animation. I first began this series when this film was

announced in 2018. Regardless of how many times he has attempted to retire,

this is the first time I’ve felt that this could be his final film. If this is

the last film of Miyazaki, and the end of Studio Ghibli itself, it is the

highest of notes that crescendos into perpetual oblivion.

REFERENCES

Arditi,

David 2021. Streaming Culture: Subscription Platforms and the Unending

Consumption of Culture United Kingdom: Emerald Publishing

_____2023.

Digital Feudalism: Creators Credit, Consumption and Capitalism United

Kingdom: Emerald Publishing

Durkheim,

Emile 2001. The Elementary Forms of

Religious Life New York: Oxford University Press.

Fraser,

Nancy 2023. Cannibal Capitalism: How our System is Devouring

Democracy, Care, and the Planet – and What We Can Do About It. New York:

Verso Books

Hirschi,

Travis. 1969. Causes of delinquency. Berkeley: University of California Press

Steinmetz,

George 2014. “The Sociology of Empires, Colonies, and Postcolonialism.” In Annual

Review of Sociology 40, pp77-103. Retrieved on 1/10/2024 Retrieved at https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043131

Weber,

Max 1956. The Sociology of Religion Boston: Beacon Press.

[1]

For the record, I think this is ingenious process of stress reduction. It seems

that Miyazaki understood that if he “retires” he does not have pressure to

answer questions about “his next film” or “what he is working on now” until he

is ready to publicly announce his next project.

[2]

The death of an artist of Miyazaki’s magnitude and caliber is such a loss it

will always seem inappropriate at any age.

[3]

Ironically, I do not thing that Miyazaki really thinks about his place in

history of culture, outside of the stories that he tells. I truly believe that

he just wants to be able to translate what is in his head rendering it into a two-dimensional

animated moving image

.jpg)