The culture of the United

States does not abide nor reckon with its history. The US cultural mindset is

one of future facing fanaticism, to the point that there is little desire or

regard for what has come before. This perspective, coupled with the stark

individualism that is birthed from the chrysalis of capitalism, has allowed for

“progress” and “prosperity” to advance, though not for everyone, and certainly

not in equal measure or based upon need. These gains are usually economic in

focus and technological in tangibility. Through this lens, history then becomes

the ends that justify the means that society never looks back on; unless the goal

is to sanitize the past to justify current social, political, or economic

conditions. Then, the interlocking institutions of power and knowledge

production merge like Voltron, to support the pro-capitalist

narrative. Film and popular culture can be a part of this institutional

“mech-ination”, especially, if it is any content that is coming out of the five

major media conglomerates, as they usually toe the line for the purpose of

profit. However, independent, self-financed auteurs usually have greater

latitude to resist the regurgitation of such wretched refuse. John Sayles’ 1996

film, Lone Star, challenges our cultural understanding and teaching of history:

especially of border town immigration, while simultaneously providing an allegorical

illustration of the history of Racism in the US through its fictional town’s three

sheriffs.

PLOT

When

the skeletal remains of a miserably racist former sheriff get uncovered on a

sunsetting military base in a small border town in Texas, the current Sherrif, Sam

Deeds (Chris Cooper) begins the investigation in earnest. Soon, the evidence

begins to implicate the town’s previous Sherriff Buddy Deeds (Mathew McConaughey),

Sam’s recently deceased father, local hero and town legend. As questions are asked and dark truths are

uncovered, Sam then needs to decide if the legacy of his father is worth

protecting; even if he knows that the man the town reveres, is more complicated

than the stories tell.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Background

Director

John Sayles is often the overlooked contemporary of the more famous 1970’s

Hollywood darlings: Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese. All were students

of “The Rodger Corman film school”. This colloquially refers to the collection

of writers, producers, actors, and directors that got their start working for

director Rodger Corman, who legendarily told every one of his new protégés that

if they work hard and are successful, they will never work for him again,

recognizing himself as a steppingstone for up-in-coming auteurs. What makes

Sayles stand out amongst the overinflated film giants revered by incel adjacent

film bros, is his commitment to social justice storytelling. Most of Sayles

work in which he both writes and directs includes politically left themes: blacklisting,

unionization,

political

corruption, pan

African -Ideals, cultural

assimilation, Disability, and Immigration

and Racism. While Coppola and Scorsese may have obscured their

themes with dynamic editing, catchy needle drops, and entertaining action,

illustrating their mistrust in the audience’s ability to sift through the

exposition to get to the symbolic gold underneath, Sayles wears his commentary

on his sleeve with every frame, (at times painstakingly) leading the audience

to the conclusion and messaging that he has laid bare before them. While subtle

in its execution, there is no questioning as to what a John Sayles movie is

about.

Conversely, Sayles’s Corman

colleagues heavily relied on depicting graphic violence with social commentary

so obtusely muddled, that film audiences would have to pan for it, as if they

were a 19th century prospector. When the audience did manage to find

little nuggets of deeper meaning, they often misinterpret it. Travis Bickel,

Michael Corleone, Tommy DeVito, and Benjamin Willard are not intended to be emulated,

but much of the young (usually white) male theatergoers continue to embrace

these aggressively toxic hyper masculine portrayals as paragons of a

mythological libertarian utopia.

Karyn Kusama recognizes John Sayles as her mentor and one of the influential people that allowed her feature film debut to get off the ground. After graduating from New York University, Kusama took on a few babysitting gigs to make ends meet. One of those jobs was for John Sayles’s assistant. According to Kusama, Sayles recognized both her talent and her potential as a filmmaker and decided to help produce her freshman film, the indie drama: Girlfight. Like Rodger Corman[1] before him, Sayles elevates those directors that he recognizes as exceptional; and with any luck, they will also not work for him ever again.

Production

Director

John Sayles originally conceived of Lone Star after he viewed the Texas

Mexico border during a cameo shoot in 1978 and went to visit the Alamo. Sayles

was fascinated with the adherence to the Alamo’s white cultural mythology and

the way that such an event could be purposefully misinterpreted and weaponized

to maintain the legacy of white cultural appropriation and colonialism,

embodied through the refrain “Remember the Alamo.” This became the catalyst for

the story in the film (Sayles, 2024). Sayles

wanted to consciously challenge the established history that supports the white

supremacist slave owning narrative; adding nuance to a subject that is often as

bifurcated as the border itself (Perez 2024). The irony of this, as Sayles

points out throughout the film’s plot, is that much like the complicated nature

of those living at the border, the border has historically been fluid; moved

and repositioned to best suit the needs and desires of those that currently

hold power and use the border as a mechanism to exercise it.

Shot on location in the

cities of Del Rio, Eagle Pass, and Laredo, Texas. John Sales sent the script

out to the locals to get both their feedback and to employ them as background

actors to add verisimilitude. This went a long way in both maintaining the

authenticity of the story, while increasing the likelihood that these cities

will embrace the production; thereby minimizing their perceived level of

inconvenience during shooting days.

One of the film’s cinematic

achievements is its use of real time, in-camera scene transitions. The film

takes place in the same town along two parallel timelines: The 1950’s past, detailing

the events leading up to the disappearance of Sherrif Charlie Wade (Kris

Kristofferson), and the film’s present day (1996), in which the investigation

of skeletal remains, commence. Since both timelines exist in the same geographic

place, often using the same setting 40 years apart, Sayles and his crew decided

to transition from the past to the present in real-time; rather than the less

interesting traditional options of cuts, fade outs, or blurring effects. Instead, the camera would fixate on an object

in a scene, say a basket of tortillas that was just brought to the table in the

present, then, in the same shot, without a cut, a hand opens the basket and

there is bribe money in it…and we are now in the past. Some of the best transitions

that Sayles and DP Stuart Dryburgh make, are the transitions where characters from

the past or present enter the frame where they typically are not supposed to be.

A shot may be holding on young Otis in the foreground, and the actor playing

Otis in the present, enters the frame in the background in the middle of a

conversation, as if he’d been retelling the scene we’ve just watched. The

camera pans quickly to him and we leave the past for the present. Several of these

exquisite compositions are of characters in the present peering back into the past.

As Hollis finishes telling a story about Buddy Deeds, the camera pans back away

from McConaughey, to center on his son Sam Deeds (Chris Cooper) in the present,

looking over his shoulder. This happens again when Sam gazes down at the water

after his conversation with Pilar. He stares into the past just as the camera

moves to reveal their younger versions.

Sam is thinking about the last time they were in this spot together. Masterful

work.

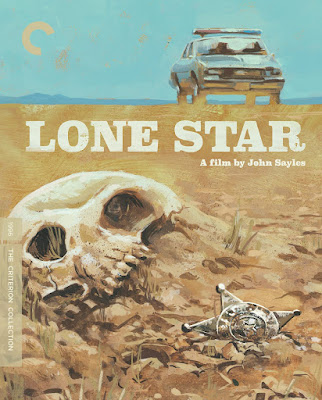

A

section on the production of John Sayles’ Lone

Star would not be complete without at least a passing

mention of the brilliance of the recently released, director approved, 4k

blu-ray release from The

Criterion Collection. Digitally remastered into a 4k

restoration from the 35mm original negative, a transfer supervised by John

Sayles and Stuart Dryburgh themselves; this film is crisp while still retaining

the feel of film grain. The image on the 4k is so sharp that this is one of the

few 4k Criterion discs that I can see a noticeable difference between the 4k

disc and its simple blu-ray companion. The clarity is so apparent on the 4k,

that the blu-ray looks like B-roll stock footage.

Another reason to buy the

4k restoration blu-ray is the insert essay “Past

is Present” by Dr. Domino Renee Perez, Professor of English at the University

of Texas. After reading this essay, I questioned the

validity and efficacy of this one. Perez (2024) engages with a lot of the same/

similar ideas the rest of this essay will interrogate. While they do not strictly

engage with the material from a Sociological perspective, their use and

understanding of history I build on and branch out from in the social analysis

section. Dr. Perez’s work is foundational to an understanding of this film and should

be considered part of the lit review for the rest of this analysis.

A Very Brief and

Incomplete Summation of US Mexico Relations and Immigration

The State government has

imposed police power to secure (and expand) the geographic region of what would

be the United States since its inception. Whether that be the securing of land

from indigenous people, the adoption of racist slave codes that began to clearly

draw the line between white and people of color populations, or the acquisition

of land as a spoil of war with the Treaty of Paris relinquishing sovereignty of

Puerto Rico to the US after the Spanish American War in 1898. The United States

internalized manifest destiny, fueled by white supremacy, consumed the

continent of land, its resources, and its people (Perea, 2021).

At the end of the Mexican-American

War (1846-1848) The Treaty of Guadalupe Hildalgo and later the Gasden Purchase

of 1853 acquired most of what is now the American Southwest from Mexico. Mexicans

that were living in areas that were now another country were promised

citizenship, full civil and property rights that were scarcely enforced; many

of them being perceived as “illegal foreigners” when the reality is, as so many

Mexicans astutely profess: “They didn’t cross the border, the border crossed them.”

(Sayles, 2024).

Those in support of the confiscating

of Mexican land as a war time trophy were, unsurprisingly, motivated by the

economic boon it would produce, and thereby perceived Mexicans and Central

Americans as a reserve labor pool. This became strengthened during the early

part of the 20th century when poverty and revolution caused Mexicans

to come into the United States for work. In 1924, the US Government exempt the

National Origins quota for Mexicans. This allowed Mexican Immigrants free entry

and return, so the US economy could capitalize upon their desperation (Perea,

2021). This set a hundred years of immigration precedence that saw the building

and thriving of entire industries (specifically in agricultural farmwork) from

the manual labor of Mexican Immigrants, and Mexican Americans. Yet, Mexican

migrants were only as valuable as the stability of the economy and the industry

in which they worked.

The acceptance or

rejection of Mexican migrants, the recognition of their human rights, and their

citizenship status is often determined by the economic need of their labor. During

the Great Depression, when the reserve labor was not needed as desperately, and

the economic justification could no longer hold the white supremacist hegemony

at bay, the US instituted a period of “Mexican repatriation” where 1 million

supposed Mexican migrants were forcefully expelled from the US. During this

process, about 60% of those expelled were American Citizens including US born

children of Mexican Immigrants. This was later followed by “Operation Wetback” in

1954 deporting another 1 million people, again many of them citizens (Perea,

2021). This has been the Mexican

immigration cycle for generations. The acceptance or rejection of Mexican

Immigrants based on economic prevalence. As the economy improved, the border opened,

as the economy declined, the border tightened.

In the mid to late 90’s (the

time when the film was both shot and released) then US president Bill Clinton expanded

deportation and demanded detention for those that were undocumented before removal.

This resulted in 12.3 million deportations and 870,000 formal removals during

his 8 years in office (Perea, 2021). The difference in this number is the legal

difference between returns and removals. “Removals” are those that are deported

from the United States under a formal order, whereas “returns” are those migrants

that are “allowed to leave voluntarily”.[2] The language of being

“allowed to leave” is far more authoritarian which would perceive “voluntary”

as a simple lack of resistance rather than an actual desire. Clinton also initiated

“Operation Gatekeeper” which began the militarization of the southern border with

more fencing and armed Border agents.

The Militarization of the

southern border[3]

of the US has compounded in the years since 9/11, the border becoming a

symbolic threat to anything within the United States (Balko 2021, Perea 2021). The US-Mexico Border was considered an ineffective

barrier in the thwarting of the 2001 terrorist attacks. Thus, “The War on Terror”

saw the increased tightening of US control over the region, culminating in a

litany of anti-immigration policies that began in the early 2000’s under George

W. Bush. This included Operation “return to sender” where Immigration and Customs

Enforcement (ICE) conducted a massive sweep of undocumented migrants on May 26th

2006. In the near 20 years since, border agencies and immigration enforcement

have been given an obscene amount of warrior style training and weaponry to “better

secure” the southern entry point into the United States.

Political conditions also

impact the flow of migrants. During President Obama’s term in office there was

a steady flow of migrant workers moving into the United States. In curbing this

flow, Obama was later dubbed: “The Deporter and Chief” for the high rate of

removals during his Presidency. When Donald Trump became President after using

anti-immigrant rhetoric, one of his first Executive Orders was the institution

of travel bans, and later, separating families at the border. These harsh and inhumane

consequences caused fewer and fewer migrants to attempt to cross during his term

(Goodman, 2021). The limiting of migrants has become politically advantageous

for Donald Trump in the current 2024 presidential election; as this rhetoric is

highly valued amongst those in his party, especially his base. Therefore, many Republican

voters will stomach his openly racist bigotry, even if they don’t agree, because

fewer migrants mean more jobs in times of economic crisis. Since 2020, both

Trump and President Biden have used the economic instability caused by the COVID-19

pandemic to restrict entry into the US almost completely. This is why capitalism

will always support fascism over socialism; because fascism does not require capitalism

to change its dehumanizing view of people to thrive; and capitalism does not

require fascism to be self-reflexive. Contrarily, fascism thrives when profit

is put over people.

Immigration in Lone Star

Immigration is the

backdrop of Lone Star. Set on a fictional Texas border town of Frontera,

the film figuratively straddles the line of those who live on either side. The

film’s depiction of immigration (outside of the racism in its enforcement) can

be seen in the character arc of Mercedes Cruz (Miriam Colon) a wealthy businesswoman

who lives on the banks of the Rio Grande. The film opens with her both

benefiting from unlawful immigration and imposing federal rules. Mrs. Cruz,

once an undocumented immigrant from Spain, is the owner and operator of one of

the most successful Mexican restaurants in town and it is implied that she

employs undocumented labor. However, when she is pressed about it by her

daughter, Pilar, she confidently declares that all her workers have “green

cards.”. That same evening, while she is out on her veranda, she notices a

couple emerge from the river and begin to run. She proceeds to call border control. Later in

the film, when she catches one of her workers helping the mother of his child

across the border, Mercedes has a change of heart and helps them into the

United States, though still insisting they speak English.

SOCIAL ANALYSIS

John

Sayles’ Lone Star, like the border town in which its set, deftly

balances the line between the nuances of race and necessary revisionist history

that allows for broader perspectives beyond just the anglicized “log line” of

mythical heroes and patriots; a subject that has become increasingly salient in

our current socio-political context, given the changes in Education law in

Texas, Florida, Alabama, and Arkansas schools.

Public Schools and the necessity of Revisionist

History

Early in Lone Star,

Pilar is overseeing a small PTA meeting of the textbook committee to discuss

course content in the school’s History class.

The white parents “express concern” with the changes that are being made

to the course materials. The proposed curriculum, which add the perspectives of

the indigenous and Mexican populations, conflict with the whitewashed

colonialist version of history the parents are more familiar with, especially the

differences between the legend and the reality of The Alamo. In this small

scene, many of the white parents express fear about the potential dangers of changing

history to be more inclusive, while using “the children” as justification for

their position and a shield against criticism for their opinions.

Some of this rhetoric includes the lines:

“History is written by the winners… its bragging

rights.”

“It’s the way it happened vs. Propaganda.”

“It’s tearing down everything in our history that we

fought and died for.”

“If we are talking about food or music, that’s ok. But

when it comes to teaching children…”

“We are just looking to provide children with a more

complete picture” [Parent interrupts] “And that is what has to Stop!”

Almost Prophetic in its accuracy, many of these phrases

and commentary on history could have been lifted from more recent debates over the

teaching of history, diversity studies programs and Critical Race Theory (CRT).

The most recent

reformation on inclusive teaching and an equitable understanding of history began

back in 2010 with Arizona

Bill 2281. This

bill attempted to outlaw Chicano Studies programs in the wake of the Tea Party

declaring a reformation on the election of President Barrack Obama as they

tried to “take the country back.” This regressive politically fueled

educational backslide continued in 2015 with the discovery of a

Texas geography Textbook that refers to Black slaves as Immigrant “Workers.” With

the election of Donald Trump the following year, there began a concerted effort

to distance and deconstruct diversity programs across the country. In 2020, Donald

Trump banned

certain types of diversity training and in the wake of the

Breonna Taylor and George Floyd Protest against police brutality,

set his sights on Critical Race Theory.

Critical Race Theory

(CRT), a multi-faceted theoretical framework in which multiple disciplines

intersect, began in the field of Law to revive activism after the 1960’s Civil Rights

Movement. From its inception, CRT recognizes the law as a type of knowledge

that constructs and reinforces our understanding about race (Ray 2022). Therefore, it also influences how race and

racial power are constructed and distributed respectively. This is done by allowing a critical

examination and challenging the traditional epistemology. CRT’s focus is to

upend the historical centrality and complicity of law in the upholding of white

supremacy and the additional hierarchies (those based on gender, sexuality,

class, age and disability) within the larger social structure.

The foundational components of CRT are as follows:

·

Race is a social construct.

·

Racism is a part of the social structure.

·

The understanding that there is little

incentive to eradicate racism because those in power gain privilege in this

system.

·

Differential racialization-

The concept that identifies and explains how every single racial and ethnic

group was marginalized and oppressed at one time throughout American history

for the betterment of people in power.

·

Intersectionality.

The valuing of the complicated entanglement of identity between race, class, gender,

sexuality, disability and how they impact access to opportunities and

resources.

·

Anti-Essentialism/

Anti Tokenism. This is the idea that there is no singular racial identity,

and that people should not be called upon, or be considered representatives of their

entire demographic identity group in which they belong.

·

There is importance in every racial and

ethnic standpoint. All racial perspectives hold some insight into the

understanding of racism.

In 2020, Donald Trump through an executive order, called

Critical Race Theory “Unamerican” (Ray 2022). Almost immediately, Trump

loyalists and other sycophantic shrills, emerged to carry this thinly veiled

bigotry to unfathomable depths. The prime targets of this irrational incandescently

incendiary ire were the foundational texts of Kimberlie

Crenshaw, and more recent firebrands Richard

Delgado and Jean Stefancic, Robin

Deangelo and Ibram

X. Kendi. Without often reading or understanding the text, elected

lawmakers at the federal and state level became Donald Trump’s foot soldiers; attacking

school curriculum, education leaders and

even future Supreme Court Justices.

Ray (2022) portends that

this attack against CRT later “metastasized into a series of broader nationalist

attacks on who belongs in a multi racial democracy” (127). As of this writing, 29

states have either entered bills, or passed legislation

attacking Diversity and Equity Initiatives (DEI), Ethnic and Diversity studies

Programs, or anything they consider “anti-woke.”[Read as “anti-white”]. Some of

the more egregious of these bills and laws came out of Texas and Florida, through

the binary Sauronic mouthpieces of Governors Greg Abbot and Ron DeSantis. Senate

Bill 17 in Texas calls for a sweeping ban of DEI programing

in public schools and universities, while eliminating race and gender based

affirmative action initiatives. In Florida, the companion bills of Senate

Bill 266 and House Bill 999 along with House Bill 7 have a litany of educational impacts:

·

Regulates how race issues can be taught in

the K-20 educational system and imposes stiff sanctions for violations.

·

Bans Critical Race Theory

·

Schools can teach about slavery and the

history of racial segregation and discrimination in an “age-appropriate

manner,” but the instruction cannot “indoctrinate or persuade students to a

particular point of view.”

·

Encourages the removal of any material

that makes white people uncomfortable.

Senate Bill 266 and House

Bill 999 go even further:

·

It demands a post tenure review policy for

public institutions.[4]

·

Calls for the elimination of DEI programs.

Recently, Florida removed

Sociology from the list of core courses for graduation at their public

colleges and universities. As with Black

studies programs in

Alabama and Arkansas before

it, one of the first steps in the elimination of a program, is eliminating its

usefulness to students in obtaining degrees. Soon, as the number of students

taking Sociology courses in Florida diminishes, low enrollment will be used as

a justification for the dissolving of the program altogether. A fundamental

part of Behavioral and Social Sciences, will soon evaporate in the “Sunshine State”

because white people feel threatened. This epitomizes a white supremacist

ideology.

According

to Perez (2024), the irony of the parallels between these regressive

educational restrictions and John Sayles

Lone Star culminated in 2021 when Texas passed the 1836

project. The brainchild of Gov. Abbot, the 1836 project

establishes an advisory committee designed to promote the state’s history to

Texas residents, largely through pamphlets given to people receiving driver’s

licenses. Part of this project was also to promote the Christian heritage of

the state as well as the suppression and removal of any material that is

considered anti-patriotic to the state of Texas. Critics also fear that the

law’s enforcement limits the way that race can be taught in schools.

Perez (2024) provides an

example that incorporates the film Lone Star:

In July 2021, the Bullock

Texas State History Museum in Austin abruptly canceled a promotional event for

the book Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of an American Myth. In it the

authors, Bryan Burrough, Chris Tomlinson, and Jason Standford argue that the

desire to preserve the institution of slavery served as a primary driver of

Texas’s bid for independence- an idea that parallels the claim made in Lone

Star by Danny Padilla (Jesse Borrego), a reporter covering the parent teacher

meeting: “The men who founded [Texas] broke from Mexico because they needed

Slavery to be legal to make a fortune in the cotton industry.” Pilar criticizes

Danny’s claim as “a bit of an oversimplification.” But the incendiary reaction

of an Anglo father, who sees Danny’s perspective as “propaganda,” reflects the

deep investment many have in the prevailing views of the Alamo.

It is in these moments, Pop culture is not only soft power, but it is prophetic.

3

Sheriffs, 3 forms of Racism

As

mentioned, Lone Star is set primarily within two time periods, the

1950’s and the 1990’s. During this time, there are three (possibly four) sheriffs

of Frontera, Texas. Each of these men represent the historical perspective of racism

at the time in which they were in power: Charlie Wade: the 1950’s, Buddy Deeds:

the 1960’s through the 80’s, Sam Deeds: 1994-1996, and possibly Officer Ray

beyond that.

Prior

to the Civil Rights movement of the 1950’s, racism, especially in small border

towns, was overt in its manifestation. Overt Racism is a type of blatant,

visible direct forms of racist beliefs (ideals), prejudice (assumptions),

expressions (micro-aggressive language) and discrimination (actions) (Bonilla

Silva 2021). This is often the type of racism that is individually focused, and

therefore the easiest to both detect and to isolate. To call Charlie Wade a

racist is an understated euphemism. He is a tyrannical egotistical white

supremacist that embodies the capitalistic dehumanization of all people;

especially those who are non-white. He is portrayed as not just the embodiment

of this form of racism, but the personification of evil. His terrorism of

nearly everyone in the town of Frontera, is designed to create a character that

is undeserving of both empathy and compassion, given his fate. He regularly verbally

accosts citizens and civilians, physically threatens them, brandishes weapons

at them, and through police discretion, under the guise of justifiable homicide,

murders people in cold blood.

In film, for racism to be

correctly called as such, even in the 1990’s, required that the kinds of racist

exploits depicted on screen, be such an exaggerated caricature that everyone in

the audience would be able to identify it. The use of such an extreme image of

racism, also gave the white audience the opportunity to distance themselves from

any possible form of racist cognitive dissonance. In the case of Lone Star,

by having Charlie Wade be the epitome of a racist white devil, it makes other

white people’s drastically less intense form(s) of racism unrecognizable by comparison.

This is played out in the context of the film when Buddy Deeds takes over as sheriff.

The power dynamics of Buddy

Deeds reign as sheriff, personifies the transition from overt racism to covert

racism after the Civil Rights Movement. Covert Racism is the invisible,

indirect forms of racism that are often imperceptible. These forms of racism

move beyond the individual into structural forms, where racism has been

normalized and baked into the social structure through social institutions’

operation and by the culture that surrounds them (Ray 2022). An additional aspect of this form of racism is

the notion of “colorblindness”. A term usually

misused by liberals and (other) white allies to connote the lack of importance

of race in the assessment of one’s character, “colorblindness” can also refer

to the labeling of the unequal racist structure as egalitarian by assuming that

it is applied to everyone equally, thereby making any visible disadvantages felt

by people of color as being the result of an individual character flaw rather

than something more systemic. This results in the obfuscation of the unequal

structure. In the film, because Buddy Deeds did not overtly threaten or murder

the townspeople of Frontera, not only were his forms of institutional structural

racism undetected or ignored, but he was deified, becoming a legend in the eyes

of the town, because he wasn’t as big as a monster by comparison. However, Buddy

would regularly manipulate people of color to get their vote (to stay in power).

He also dammed up a river to create a lake that cut off water to an entire town

of mostly migrant people; and utilized migrant prison labor to build personal

and community projects. There was even some indication that Buddy Deeds would

have advised against interracial dating in the town[5]. Buddy was a hero, only

because Charlie was a ghoul.

Sam Deeds is supposed to

be a modern white ally, except his allyship only moves as far as his own self-interests

motivate him. At the beginning of the film, Sam does not believe the hype about

his father. This lack of belief is not motivated by a desire for the truth, but

by the desire to prove his father wrong and to expose him as a fraud,

vindicating Sam for a personal slight his father inflicted on him when he was a

child. Sam cares about the displaced Mexican people, the use of prison labor,

and the restrictions on interracial dating in the town only when he is still

mad at his father. When Sam finds out the truth about Charlie Wade’s

disappearance, Buddy’s relationship with Mercedes Cruz and Pilar’s true parentage,

the value of exposing Buddy’s use of systemic racism to maintain power, is no

longer personally advantageous; therefore, he ignores it. This ignorance is

illustrated when Hollis tells Sam that his father will be blamed for Charlie

Wade’s murder. Sam blandly replies:

“Buddy Deeds is a legend. I think he can handle it.” Thus, rather than white

allyship, Sam represents the average non marginalized voter in the United

States.

For many non-marginalized

people (upper class, white, male, heterosexual, able bodied individuals), their

care and compassion rarely extend past the people in their own private lives,

and on the rare chance that it does, their outrage is often performative. The

truth of this is evidenced by the way that many people do not fight for the

social justice of others if they are not personally benefiting or impacted through

relatives, friends or loved ones. Secondarily, these same people perceive a

protest with the same importance and enthusiasm as a form of entertainment. In

fact, those with one or many roads of access to power and stability often perceive

civil disobedience as just another form of “activity “to stave off boredom. This alludes to the way that the social

structure socializes non-marginalized people (especially) into a practiced apathy

that allows the system to continue without being challenged.

This apathy, motivated by

convenience and self-preservation, becomes many people’s default setting. Our

individualist capitalist culture has conditioned its people to be

self-motivated, to see relationships as transactional and to acquire as much

power, money, and status to generate social stability. However, that stability

comes at the cost of collectivist unity and social solidarity. The more a

system grants access to opportunities and resources for success, the less

likely those that are granted access will want to change it; self-preservation,

they have too much invested in the system to truly seek its change. Similarly,

the quickest pathway to social apathy is through the development and

maintenance of routines that anesthetize people into ritualized states of being

which mirror lucid dreaming (Weber 2019). Thus, any break in such a routine is

equivalent to shaking someone awake, which accounts for the myriad of examples

of irrational outbursts by privileged people over the smallest inconvenience or

disruption. They don’t like the world being reflected back at them. They’d

rather be asleep.

We are only given a glimpse of the potential fourth sheriff of Frontera, Ray, the town’s first non-white law enforcement leader. While many of the white townspeople lament this inevitability, believing that it will be detrimental to their way of living, (inconvenience) one conversation with Sam Deeds dispels this racially charged unsubstantiated fear. When Ray makes Sam aware that Ray is being groomed to be the Next Sheriff by the white business leaders in town, Sam asks Ray what he thinks about needing a new jail (something that Sam currently opposes). After Ray gives Sam a perfectly political non-answer, Sam snarkily remarks that he thinks Ray will make a great Sheriff. This indicates that the powerful white business owners of Frontera plan on propping up a person of color in the position of sheriff to maintain, and with the new jail project, possibly expand their influence over the town; Ray being the tokenism that masks white supremacist power and authority underneath.

Blackness in Lone Star

One

of the central narrative themes of Lone Star revolves around fathers and

sons. While the focus of the film’s engagement is on the relationship between Buddy

and Sam Deeds, the film also elliptically includes the pair of Otis and Delmore

Payne, through which the film engages with Blackness in the US and the often-forgotten

Black indigenous population. In the present narrative, Otis (Ron Canada) is

introduced in the film as one of the power brokers in Frontera. He is

colloquially referred to as “The Mayor of Dark Town” who provides a safe haven

for Black people in the border town including soldiers at a nearby base. His

recounting of his experiences with Charlie Wade when he was younger becomes

important to unraveling the mystery of Charlie’s disappearance. Delmore (Joe

Morton) is introduced separately as the new Commanding Officer of the Army base

that is slowly getting phased out. His introductory speech to his soldiers confirms

that he is a tough but fair man, by the book. It isn’t revealed until later in

the film that the two are related, and only through dialogue and exposition do

we understand the nature of their relationship, which is strained. While they

share little screen time, the exploration of Blackness is through these men’s

relationship and interactions with two other younger Black characters: Otis

with his grandson, Chet (Eddie Robinson), and Delmore with one of his soldiers,

Athena Johnson (Chandra Wilson).

Regardless

of the strained relationship between his father and his grandfather, Chet Payne

seeks out a relationship with Otis when they first arrive in town. Through a

series of conversations, Otis gives Chet a brief history of Black

Seminoles; escaped slaves who fled to Florida, a free

Spanish settlement at the time, and

fought against colonialization. Historically, similar experiences were quite

common. Slave revolts were often bolstered by the indigenous population, and

once free, former slaves would join native people in various assaults on the

American Colonies, although some Southern Indigenous People were also

slaveholders. The primary reason for this dissonance is the Indigenous people’s

rejection of white supremacy, yet still associating blackness with slavery (Kendi

2016). While hypocrifully incongruent,

the fight against injustice often makes for some unlikely and strange

bedfellows. As the conversation

continues, Sayles, as a writer, juxtaposes the importance of familial

relationships, with how biology was used to dehumanize Black slaves as being

literally perceived as less human (3/5th- “one drop rule”) with

Otis’s statement to Chet “Blood only means what you let it.”(Sayles 2024).

Perez (2024) feels the weight of the history of that line, perceiving the

untangling of history as akin to bloodletting: “the act can be healthy

cleansing, liberating, or it can open an old wound, causing pain, anew.”

This

bloodletting is again invoked when Chet talks about Delmore being an

overbearing father. “It’s like with each new medal he had to ratchet himself

tighter, and that went all the way down the chain, to us.” (Sayles 2024). While

Chet blames his father’s disposition on Otis’s absence from Delmore’s life, this

also could be a function of living in racism and institutions of white

supremacy. The most sociological part of an epigenetic argument for the impact

of racism on the human body is the overall effect of stress it causes, called “weathering”

,

and the arc of Black decision making that has to account for racism. From deciding

when to let your kids drive, to taking a particular job, racism permeates Black

people’s lives, minds, and bodies. In this context, Delmore’s actions can be

understood. Add to this the complication of the tokenism of a Black man in

Military authority, and his actions are not just understandable, but justified.

Delmore’s disciplined demeanor

is further explored and cracks through his conversations with Athena Johnson, a

soldier under his command, who was a witness to a shooting at Otis’s club.

Athena’s drug use at the club threatens her place in the Army. It is also alluded

to that Athena joined the Army to get out of an economically impoverished, and

possibly dangerous neighborhood. This is representative of Black people being historically

overrepresented in poverty rates, and one avenue open to Black People to

achieve a middle-class lifestyle is to join the Military and access the

benefits afforded to them by the GI bill (Desmond 2023, Rosthstein 2017). Consequently,

this also gave the Military Black soldiers that they could use

as cannon fodder…an action that

has historical precedence.

In the film, Athena

clearly articulates this:

- Delmore

Payne: With your attitude, Private, I'm surprised you

want to stay in the service.

- Athena

Johnson: I do, sir.

- Delmore

Payne: Because it's a job?

- Athena

Johnson: Outside... it's... it's such a

mess. Um... It's...

- Delmore

Payne: Chaos. Why do you think they let us in on the

deal?

- Athena

Johnson: 'Cause they got people to fight -

Arabs, yellow people, whatever. Might as well use us?

A culture of White Supremacy is illustrated when, to

escape economic strife and drug addiction, one of the limited avenues a Black

person has for success is to join the military; thereby using their bodies to

the benefit of the US government, with the promise that after your time is

served, you will achieve financial stability. This is done with a duplicitous

lack of acknowledgment that those same conditions that lead Black people to

join were created through the compounding historical practices of slavery, sharecropping,

the elimination and erosion of black wealth, and the criminalizing of nonviolent

drug offences leading to mass incarceration.

CONCLUSION

John

Sayles’ Lone Star is an independent cinematic masterpiece. It weaves

social commentary and complex themes with the pathos of a drama that grips you

until its final frame. A lot of the arguments covered in this essay remain

timely, in part because Sayles was interested in social justice issues at a

time when many other mainstream auteurs were not, and because history rhymes. Salient

social commentary is renewed whenever there is a novel context, usually sparked

by a current event. This film, like a lot of pop culture, will remain a digestible

way to engage with these ideas without full commitment to social Justice; but

with a little luck, it can become a gateway.

REFERENCES

Balko,

Radley 2021. The Rise of the Warrior

Cop: The Militarization of America’s Police Forces. New York: Public

Affairs.

Bonilla-Silva,

Eduardo 2021. Racism without Racists: Color-Blind Racism

and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America 6th eds. New

York: Rowman and Littlefield.

Desmond,

Mathew 2023. Poverty, By America. New York: Crown Publishing

Goodman,

Carly 2021. “Unmaking the Nation of Immigrants: How John Tanton’s Network of

Organizations Transformed Policy and Politics.” In A

Field Guide to White Supremacy Kathleen Belew and Ramon A. Guitierrez.

Oakland: University of California Press.

Kendi,

Ibram X. 2016. Stamped From the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist

Ideas in America New York: Bold Type Books.

Perea,

Juan F. 2021. “Policing the Boundaries of the White Republic: From Slave Codes

to Mass Deportations.” In A Field Guide to White Supremacy Kathleen

Belew and Ramon A. Guitierrez. Oakland: University of California Press.

Perez, Domino Rene 2024. “Lone Star: Past is

Present.” In Current. New York: Criterion Collection. Retrieved on

4/26/24 Retrieved at: https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/8358-lone-star-past-is-present

Ray,

Victor 2022. On Critical Race Theory: Why it Matters and Why You Should Care

New York: Random House.

Rothstein,

Richard 2017. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How the Government

Segregated America New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation

Sayles,

John 2024. Lone Star. New York: Criterion Collection

Weber,

Max 2019. Economy and Society A New

Translation Cambridge. Harvard University Press.

[1] At

the time of writing this sentence, Rodger Corman was still alive. RIP the

legend

[2] It

is unclear as to what “voluntary” means in this context. Preferably there needs

to be a distinction between willingness and “not resisting” while the word implies

the former, it is more likely that the legal definition also includes the

latter.

[3] colloquially

referred to as just “The Border” because it is the focus of immigration policy

and thinly veiled white supremacist ire

[4] It

is heavily implied that this is implemented as a witch hunt for Professors with

tenure protection who teach about structural racism and institutional sexism

amongst other topics considered “Woke”

[5] This could be a case of the unreliable

narrator given that the individual in question may be referencing the way Buddy

Deeds did not want his son, Sam, dating Pilar, assuming that it was because of

their racial differences when the reality was that they both have Buddy Deeds

as a biological father.