The 12th film

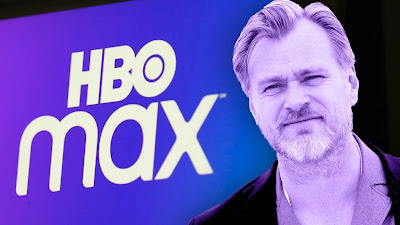

in my continuing analysis of The Films of Christopher Nolan, is the WWII biopic

Oppenheimer. Still reeling from his inability to “save cinema” with the

release of his previous venture, Tenet, Nolan is given another bite at

the apple from Universal Pictures, after he burned the Warner bros bridge

because of HBOMAX (Now just Max *eye roll).

Rather than have any kind of clear or compelling understanding of

history, the audience for Oppenheimer is treated to a well shot, overly

edited piece of Pro War disjointed propaganda that has nothing to say about

morality and genocide, while still treating his female characters as two-dimensional

fridge victims despite their real-world accomplishments. This film is a love

letter to those white male dads who got into WWII when they became parents,

thoroughly validating their overinflated sense of nationalism. For the rest of

us, or those of us that don’t exalt that identity, Oppenheimer is an

arduously long, repetitive slog into the worst parts of humanity and

masculinity, while reveling in its self-delusion of nuanced benevolence.

PLOT

After experiencing

anxiety over performing lab work, doctoral student J. Robert Oppenheimer pivots

to theoretical physics, where he eventually achieves a Ph.D. Later in 1941, he

is tasked by the United States Army to enter a nuclear Arms race with Nazi

Germany. The successful test and use of the Atomic Bomb causes public backlash

resulting in Oppenheimer being subjected to a political and judicial inquiry where

a lot of his personal foibles, infidelity and political ties are revealed to discredit

him.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Based

on the book American Prometheus by Kai Bird and Martin Shewin, Nolan’s

script seems to be historically accurate in broad strokes and faithful to its

source material, minus some dramatic license in its narrative. What is more

alarming is not the minor inaccuracies of who said what when, or where

someone’s hand placement was, it is what this film leaves out.[1] There is little to no

mention of the effect the events of the film had on other people; especially those

living in the area where the Los Alamos Laboratory was built, and the literal

fallout of the Trinity test itself.

Tina

Cordova’s article in The New York Times elucidates the

vacuous absence of the direct consequences of the US development of nuclear

weapons in Nolan’s film. There is no mention on the razing of farmers land in

the region to build the laboratory and mine uranium through eminent domain, the

government’s ability to take private property for public use. Cordova also

points out that there were 13,000 people living within a 50-mile radius when

the nuclear test was conducted, who are still waiting to be recognized and

compensated through the Radiation Exposer Compensation Act set to expire in

2024. The

film’s omission of this displacement, danger to the populace, and lack of

clarity on how the project was obscured for those that worked on it by Military

leaders, ultimately sanitizes these events[2].

Where the lab was built, and the test conducted, Nolan treats his audience to

nothing but empty land. Like a lot of films set in the open plains and the American

Southwest (there is a whole

genre with this backdrop) there is always empty land space without reminding

movie going audiences how that space became empty in the first

place.

Pop culture is Soft Power. It shapes the way

that we experience and understand the world, in part, through its sheer volume

of content. The multitude of films that depict the United States, especially

certain regions, as devoid of everything, save geographic resources, compared

to a few handfuls of books, articles and (usually) documentaries that explain

how that space became vacant; overrides the public consciousness from the

truth, and reinforces a Pro War Image that has long history in our entertainment.

In a previous

essay I explained the relationship between the Military

Industrial complex and entertainment in this way:

In 1956, Sociologist C.

Wright Mills in his book The Power Elite discussed the collusion of the three

powerful social institutions in the United States, that of the Military, the

Economy and The Government. The name for this collusion, the Military

Industrial Complex, was attributed to Dwight D. Eisenhower during his farewell

presidential address in 1961. What was considerably absent from this analysis,

that was later filled in by other scholars in the interim, was the overall role

of the media in this enterprise.

The role of the media, and more specifically

Hollywood, in the overall interconnection between these powerful systems is as

a propaganda machine and recruitment tool. Since World War II, the media has

been used to not only shape the public opinion about war, but to also provide

the Military with large numbers of young, able-bodied recruits. Many of these

tactics include but are not limited to: fear mongering (through news media), a

sense of cultural pride (through an appeal to nationalism), to expressions of

gender (combining militarization with masculinity) and economic stability (GI

Bill and the Poor). This has led to the entire entertainment industry, from

books and films to television and video games, to be linked with the military

and the broader department of defense. This Hollywood connection has been

disparagingly referred to as “The Military-Entertainment Industrial complex” or

more succinctly, “Militainment”.

According to Rebecca

Keegan (2011):

Filmmakers gain access to

equipment, locations, personnel and information that lend their productions

authenticity, while the armed forces get some measure of control over how

they’re depicted. That’s important not just for recruiting but also for guiding

the behavior of current troops and appealing to the U.S. taxpayers who foot the

bills.

Thereby many films, TV

show episodes or Video Games that are about, or feature, any aspect of the

military (regardless of genre) will have a military consultant assigned to them

if the filmmakers want to keep their overall costs down.

The development of this

relationship between entertainment and the military began in early Hollywood

with film directors making legitimate Propaganda films in the 1940’s (look at

Frank Capra’s film: “Why We Fight.”). This continued through the 1950’s and

60’s with the films of John Wayne, members of the Rat Pack and Elvis. Yet, this

collusion wasn’t solidified until the Reaganite 80’s with the release of Top

Gun in 1986. The Navy was heavily involved with the film as a consultant

ultimately increasing Navy recruitment by a staggering, but yet

unsubstantiated, 500%. Thirty-five years later, that link is still strong with

its sequel Top Gun: Maverick not only being nominated for best picture but

praised as being the film that saved theaters after the COVID-19 lockdown. Any

film that is contentious, or critical of the military and its mission, will not

get support. Oliver Stone had a very difficult time getting his films Platoon

and Born on the Fourth of July funded because the military rejected his funding

requests given the depiction of the Military in those films.

Nolan’s decision to direct a period piece and further

whitewashing that time period contributes to and classifies Oppenheimer as

“Militainment.” US focused WWII stories have always been a soft-landing point

for military propaganda due to it being the birth of the American war machine. It

is a time that we’ve disinfected from the realities of protest or derision to manufacture

public support. Even today, these stories are still a hook for a lot of

older white male theatergoers that buy into the myth of American Greatness; thereby

developing an unhealthy interest, bordering on obsession, with “The Greatest

Generation” convincing themselves it was a time when “America was Great.”

*eyeroll*. Clearly, Nolan got support from the Military for this film as he was

given permission to film the explosion on White Sands Missile Range even if he

didn’t use it. The military officials must have not been threatened by the script,

believing it would show the American Government in a positive light.

Furthermore,

since we’ve seen a rise in, and desire for, diverse representation on film and

in other forms of media, we’ve also seen a rise in white male directors retreat

into the period piece. That way, their penchant for hiring (and telling stories

about) white men is obscured by the era when their story is set. This has the

added effect of veiling any racial ignorance/racism they may have; as well as shield

them from obsolescence in the current progressive culture.[3] This retreat from

criticism is even illustrated in the stories that these white male directors decide

to tell[4]. For Nolan in this film, he

skirts the surface of critical analysis for J Robert Oppenheimer without producing

anything of substance. Like a lot of Right-wing pundits and the “discourse”

coming out of the libertarian movement, Oppenheimer depicts white men

engaging in lazy, inconsequential thought from a safe distance. These stories

often do not engage with their subject in any meaningful way. Instead, many of

these recent white male focused period pieces, play fast and loose with history

to the point where they should be considered fantasy or science fiction. This

inevitably comes across as teenagers writing collective fan fiction, building

on each other’s statements by saying: “Wouldn’t it be cool if…”. The problem, however,

is the unlikelihood that the audience for Oppenheimer recognizes the

difference between fact and fantasy. This is especially murky given Nolan’s

reputation for “gritty realism”. The public do not know, or aren’t prepared,

when Nolan takes such liberties, stretches truths, and tips his hand into the absurd.

For instance, the cringe inducing moment when Nolan uses Oppenheimer’s famous

quote: “I have become death; destroyer of worlds.” as sexual foreplay. This context

robs the quote of any pathos. Instead, it is a sophomorically pithy deflection

and deflation of reality while also hypocritically undermining the very “seriousness”

Nolan is evangelized for. This shows that Nolan only wants to be perceived as being

inquisitive without any real contemplation.

Sociological

Aside: Theory and Research

In Sociology, a theory is

a statement about how particular facts are related that is often explaining social

behavior usually through the lens of a theoretical perspective. Sociologists

usually talk about “The big three” theoretical perspectives (Structural

Functionalism, Symbolic Interactionism and Power/Conflict) while others are adjacent

and incorporated (Post Structuralism, Feminist Theory, and Critical Race

Theory). Each of these perspectives act as a blueprint and or model for how the

social world operates and exists; and while the derivative individual theories

of each perspective will be explaining the same behavior, the conclusions are

going to be different because of the lens with which they are observing the

world.

The relationship between theory and research

is symbiotic. You cannot have one without the other. It is obvious you need a

hypothesis born out of theoretical analysis to test ideas. However, for a

theory to be viable, it first needs to be based on observable evidence. Otherwise,

why does it need to be explained? It is through the curiosity generated from

the observation that theory is born. Theory is not fabricated; it is the

attempt to understand the order of things and requires research. This continues

through the Scientific Model allowing the theory to be tested through a variety

of research methods either from the quantitative branch, broad numerical

approach, or the qualitative branch, which is far more descriptive and

detailed. Once the observation informs

the idea, through research, the data informs the theory. Does the theory need

to be changed to account for the results of the test? Usually, yes. Those

changes then allow the theoretical analysis to build. This is not what happens

in Oppenheimer. I take great umbrage with the way that this film scathes

the importance of theory and research.

At the beginning of the film, Oppenheimer is seen struggling in the laboratory. It is heavily implied, and later, directly stated, that he is terrible at scientific lab work. Because the University does not want to “waste his mind”, it encourages him to transition to Theoretical Physics. This makes the unintentional consequence of valuing research results over theory. The University is just going to stick him in his own theoretical corner until one of his ideas can be usable for a practical purpose. Rather than reinforce this division between theory and research, the film could have done something different. Imagine if the film leaned into his incompetence at lab work which then shed some doubt on his ability to help generate the bomb successfully, adding to the tension; and reinforcing the importance of both theory and research. Instead, that drama is minimized through a cheeky conversation between Leslie Groves (Matt Damon) and Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) which doubles down on the devaluing of theory and reduces the importance of research with the line: “What do you want from theory alone?”

Meanwhile, the actual Oppenheimer said:

Production

Nolan has

long been interested in doing his version of a biopic. For years, he was interested

in adapting the life of Howard Hughs, but was beaten to the screen by Martin

Scorsese with The Aviator. It is unclear if his fascination with

Oppenheimer was concurrent with his development of the Hughes story, or if became

a more recent interest with the publishing of

the source material, American Prometheus, which

Nolan read in 2019. With Robert Pattinson’s Tenet wrap

gift to Nolan being a book of Oppenheimer speeches, it seemed like the subject

of Nolan’s next project was set. Yet, as the planning for what would become Oppenheimer

began, Nolan’s relationship with Warner Bros soured due to their 2021

release schedule in conjunction with then titled streaming service HBOMAX.

In my

previous essay on Tenet I

wrote:

There

has been a lot of negative reactions to the AT&T decision in the last few

months, many of them coming from people who stand to lose a lot of money with

this decision; namely directors

and actors (who’s pay scale may be tied to box office performance) and Theater

owners. One of the most vocal about this decision

was Christopher Nolan himself, who’s relationship with Warner bros. up to this

point was so strong, that he is one of three directors (The other two being

Clint Eastwood and Todd Philips) that could make whatever they wanted without

studio interference.[5] This relationship was immediately

put into jeopardy when Nolan criticized the decision for not including

filmmakers in the conversation. In

an interview he was quoted as saying

“Filmmakers went to bed the night before

thinking they were working for the greatest studio, and when they woke up they

realized they were working for the worst streaming service. Warner Bros. had an

incredible machine for getting a filmmaker’s work out everywhere, both in

theaters and in the home, and they are dismantling it as we speak. They don’t

even understand what they’re losing. Their decision makes no economic sense,

and even the most casual Wall Street investor can see the difference between disruption

and dysfunction.”

With such a statement it is clear that

Nolan was so burned by this decision, as a clear anathema, and bane of his

existence, that he

has decided to completely sever ties with Warner Bros.

a studio he has worked with since 2002 and where he reigned supreme, along with

Eastwood and Philips, as Warner’s Directing holy trinity. It is

clear with his clout in Hollywood, and now evidence of principle consistency

and having the “courage of his convictions”, Nolan will be able to produce and

distribute his film anywhere he wants. It has yet to be determined

who the real losers in this exchange are. The unknown variable is the complete

and long-lasting economic impact of COVID 19. AT&T’s decision may be the

best for them in the short term (which is typically how large corporations

think) But Warner Bros will not be able to ride the Nolan gravy train to the

next station, as long as he keeps making films that people want to

see. In the case of Tenet, the convoluted nature of the

film’s plot and the difficult social conditions of the industry upon its release

created a perfect storm of complications that led to this film’s overall

failure.

This led Nolan to go to Universal Studios for Oppenheimer,

getting a “Blank

Check” for his trouble, and being allowed to extend the theatrical

window for the film from the standard 90 days to 120. Thus, Nolan was a “studio

darling” again without any oversight. To keep his position as the studio

paragon, Nolan again brought the film in early and under budget. While this may

ingratiate himself to the producers, and the studio financing the film (like

Neo, he is “the one), this can also put a strain on the workers; especially

considering that Oppenheimer

was

shot in 57 days: beginning in March 8th2022

and ending that May. Because of this self-imposed timeline, corners were cut, labor

was not valued, and three thread bare story concepts, unable to stand on their

own, were twisted together in a contrivedly convoluted claptrap that one could

barely call cinema.

In

the truncated timeline of Oppenheimer, the set for Los Alamos took 6

months to build but was only used for 6 days of actual shooting. While this is

often common in a lot of Big Budget films, it speaks to the frivolity of spending

when your budget is the equivalent of the infinity symbol. This also has the

added implication of the transient nature of background labor in Hollywood, and

the lack of compassion for production and postproduction labor. This mentality is the underline problem that

has led to

the ongoing Writers and Actor’s strike.

Additionally,

because Nolan is perceived and self-promoted to be a chiefly technical director,

little regard is shown for story and dialogue.

This is initially evidenced by Nolan’s fascination with cinematography

and scene composition, manifesting itself through his obsession with IMAX

cameras. The camera’s being notoriously

loud, a lot of the dialogue gets drowned out. On another film, that wasn’t

overly fixated on a single part of the filmmaking tapestry, this draw back

would be fixed with Audio Dialogue Replacement (ADR) requiring actors to come

back and redub their lines to provide a film with cleaner audio.

But in a Nolan film, that is not happening. In

a recent interview Nolan rejected the use of ADR

because he “wanted to preserve the actor’s performance on set.”. But on Oppenheimer,

Nolan goes a step further to obscure his dialogue by maintaining a score in

the background even in a simple two shot dramatic scene in an office. The only

time that Nolan’s film is noticeably silent is in the authentic depiction of

the bomb’s explosion, which sees a noticeable time lapse between the flash of

the explosion and its delayed cacophonous resonance. Whether this is another

instance of Nolan’s preoccupation with style over substance, or an active obfuscation

of trivial and puerile dialogue is unclear, but possible.

Nolan’s

contempt for anything outside of his beloved shot composition is observed nowhere

more clearly than his inability to tell a linearly rich and detailed story.

Instead, Nolan chooses to weave disparate fibers of uncomplicated and

rudimentary storylines into an unnecessarily complex web of scenes/images, that

are cut together with such rapidity, that the audience does not know what

exactly they are watching. In Oppenheimer, Nolan cannot help himself

from trying to connect three simple linear parts of Oppenheimer’s life: His

romantic relationships, His work on the bomb, and his political persecution

afterwards, into an inconceivably incongruous mess of nonlinear spaghetti; each

storyline thin and unsatisfying by the end. To be fair, in past films, such as Memento,

The

Prestige and Inception,

this style has worked for Nolan given the genres he was playing in. This style

becomes increasingly unnerving and frustrating when working in the genre of historical

Biopic.

It is

unclear how much Nolan is a man who sees the world outside of his own

perspective. He often tells the same story and wrestles with the same themes

that shallowly speak to him as a well off British American white dude. Like a

lot of other up incoming auteurs of the 1990’s, including the likes of

Tarantino (*groan*), Nolan prides himself for never going to film school and being

able to go to every department and understand what they do; learning how to

make films by going out and making them. The problem with this self-made,

pro-meritocracy, bootstrap pulling bullshit is that does not recognize the

opportunities, assistance and support Nolan, and others of his ilk, got from

countless other people behind them. They are under the false consciousness that

they did it all themselves, and that they are the most important person in the

room. This is a common mentality that feeds the egoistic narcissism of young

male directors. At which point the directors are surrounded by so many

sycophantic suck-ups that they are never challenged in any meaningful way.

SOCIAL ANALYSIS

Being a specifically

rooted biopic of a person in a significant time period, Oppenheimer becomes

less sociologically interesting outside of its historical context. What is

compelling is not the themes of the film, but how those themes were used to

market the film to the public, and the film’s ultimate consumption. In the age

of low theater attendance and viral media marketing campaigns, Oppenheimer became

ensnared in a box office battle, turned friendly rivalry, that ironically deconstructed

and laid bare one of Nolan’s greatest screenwriting weaknesses.

“Barbenheimer” and the Bechdel Test

When

Christopher Nolan had his falling out with Warner Bros over the HBOMAX deal, that

left a hole in Warner Schedule of programming that was originally reserved for

Nolan. However, because Nolan could

pretty much write his own ticket at Universal he decided to keep with the

originally planned third week in July release date (a staple for Nolan). Still,

in a petty move of counterprograming, Warner Bros slated Greta Gerwig’s Barbie

the same weekend as Oppenheimer, and thus, “ Barbenheimer”

was born.

Initially,

the media manufactured these films as rivals. They initially saw the behind-the-scenes

drama between Nolan and WB, and the overall thematic differences between

the films, as being ripe with contentious drama. Yet, as this comparison went viral, creating

companion memes galore, it became less about box office competition and more

about what is the proper viewing order. Were you going to see Oppenheimer first

to get the serious heft of a WWII era Biopic out of your system and then finish

it up with a bubble gum chaser of Barbie? Or were you going to see them

in reverse. The irony, to anyone who has seen both films, is that Gerwig’s Barbie

is a lot more nuanced. It attempts to maintain a feminist lens that dismantles

gender norms and the patriarchy; ultimately revealing itself to be a lot more

cerebral than originally perceived.

It

would be easy to frame these two films along the gender binary and say that Barbie,

with its loud neon pink saturation, and collection of racially diverse female

cast, is about women, and that Oppenheimer is about men. Yet, Barbie says

more about toxic masculinity and how to heal from it, whereas Oppenheimer just

doubles down on the poison. This persistence for the film to have no self-awareness,

in comparison to Barbie which is cheekily self-aware, highlights Oppenheimer’s

deaf tone with audiences, especially around the writing and

characterization of women.

Christopher

Nolan has never been able to write women, and as a result women are little more

than window dressing in his movies. Few

of Nolan’s films pass The Bechdel Test, a simple low bar of female

representation in film that has three basic components:

1. There

are two women in the film that have names.

2. Those

women talk to each other.

3. The

subject of their conversation is not men, or a male character.

This measurement is not determining a film to be

feminist or even good. Many of the films that pass can still be sexist, while

other films with an egalitarian message can fail. It is a just a foundational measurement for

the perception of women in filmmaking; but it is surprising how many films fumble

this criterion.

In Oppenheimer, Nolan

seems to have regressed from recent work to present women more unfavorably than

before. There are two principal female characters in the film, each of whom are

framed only as a love interest for Oppenheimer, even though the women being

portrayed: Jean

Tatlock (Florance Pugh) and Kathrine

Oppenheimer (Emily Blunt), were far more interesting

and accomplished in their own lives beyond their relationship with Oppenheimer.

Yet, Nolan sees these accomplished women as nothing

more than the motivation that drives his protagonist and the source of shame

and guilt that haunts him. What

makes this film different than the countless other 2-dimensional carboard props,

Nolan usually creates of his female characters, is that in Oppenheimer, he

adds nudity and sex. At least 1/3rd of Florance Pugh’s screen time

is spent nude, and with the stilted jolting cuts that Nolan loves to make, most

of her screen time is just visualized parts of her body. Understand, nudity and sex are not the

problem. But add female nudity and sex to the already reduced myopic vision of

women to begin with, then you are just recreating tired and objectifying

stereotypes.

CONCLUSION

Christopher Nolan retreads a lot of the same ground in his films, often using the same actors to go through the same notes of time, loss, regret, and redemption, to usually financial and critical success. In addition to pointing out Nolan’s narrowed interests in storytelling, this also points to the way that our culture has been conditioned through Bureaucratic socialization to want a remixing of certain stories, rather than new ones. This is made heart-wrenchingly clear with the proliferation of legacy sequels, IP adaptations, and forever franchises that have become so much cash cow content that the public becomes desensitized to it. It just becomes something to watch. In this landscape, no one cares what they are eating, so long as the troth is full. The problem, aside from the obvious slow corrupting death of a hundred-year artform, is that Nolan’s work looks like the peak of cinema by comparison. Use older techniques that bid time return and frame your film in a different way than the countless hours of churned out drivel from every production company, and suddenly you are evangelized as a god. Like this film’s subject, Nolan believes himself to be divine, graciously giving the gift of “real” cinema to the people, when, his reverence is a function of the quality of cinema decreasing, rather than his work shining above the rest. His work profits from lowered expectations which also shields him from mainstream criticism and growth as a filmmaker. Oppenheimer is a culmination of a lot of Nolan’s worst tendencies, and without honest introspection, he will become what the indie film bros. of the 1970’s became: bloated human husks of corporately controlled power, that strangled the very thing they claim to love.

[1] As

a geek and film snob, I know what it is like to get very granular with things

that you are interested in.

[2] Those

in authority literally called the bomb a “gadget” Meanwhile, their many other

employees had no clue what they were working on until Truman’s announcement of the

attack on Hiroshima.

[3] Scorsese,

Tarantino and Nolan have all done this in recent projects.

[4] These

characters are usually a thin veneer atop the director’s own collection of

neurosis and narcissism that they are publicly trying to work through.