In the organization of

traditional gender stereotypes, masculinity is framed as the rational

(emotionally) repressive and relationally reductive identity that thrives on

aggression as well as the alienation and abuse of women. Women, thereby become

the fulcrum and rubric by which men ocellate toward and are critiqued; to

achieve and maintain their traditional forms of (fragile) masculinity.

Conversely, in this same organization, femininity revels in the relational,

having women define their identity through the emotional bonds they cultivate

with their children or the variety of male figures in their lives, albethey

fathers, mentors, or partners. The

normalization of this framing happens through its consistent representation in

film and popular culture. Under this yoke, not only do we see a reproduction of

these dangerous archetypes, but there is little room for exploration past these

boundaries, unless there’s a monumental catalyst. Ridley Scott’s 1991 Thelma

and Louise is the frenetic feminist film about friendship that became the

popular spark for the third wave feminist movement, upended traditional gender

role organization in cinema, and galvanized a generation (of women). This paper

is a brief exploration of the social and cultural impact of the film, its

resonance, relevant themes, and reclamation by both the industry and

populace.

PLOT

While traveling to a fishing

cabin for a weekend getaway, two girlfriends stop at a roadside bar to get a

drink and proverbially let their hair down. However, after experiencing an assault

and attempted rape that leaves the rapist dead, the titular Thelma (Geena Davis)

and Louise (Susan Sarandon) flee the scene; understanding that they will not be

believed or found innocent. What follows is a road-trip across the southwest as

the pair attempt to get to Mexico while trying to avoid a tenacious cop (Harvey

Keitel) and the FBI hot on their trail.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Since

its release in 1991, Thelma and Louise’s cinematic gravitas has been

profound. This praise being validated in 2016 when the film was entered into

the library of congress as a work that was “culturally, historically or

aesthetically significant.” Screenwriter Callie Khouri’s female led “buddy road

trip” movie both subverted and exceeded expectations. The film acts as a

barometer for the time period from which it is currently being analyzed. The

feminism, and barriers that were present at the time of production and the

initial reviews, have different arguments for the film’s merits and shortcomings

than those who view the film retrospectively.

What was harsh criticism and resistance in the early 1990’s, may be

nostalgically tempered today; even perceived as quaint. It is also important to

recognize that Thelma and Louise is a seminally foundational film from

which other filmmakers have scaffolded and parodied in the warmest heartfelt

way

Production

Callie Khouri originally

planned for Thelma and Louise to be an independent film, with herself

serving as writer/director. But after shopping it around and finding no buyers,

her producing partner arranged to have the script find its way (through a

series of acquaintances) to Ridley Scott. Scott loved the script and bought the

film rights for $500,000. Scott only decided to direct the film after Michelle

Pfeiffer convinced him; she and Jodie foster were originally going to star in

the film. Both would eventually drop out due to scheduling conflicts with other

projects: Pfeiffer went on to star in Love Field and Foster went on to

her award-winning turn as Clarice Starling in The Silence of the Lambs.

After their departure, other actors under consideration were Meryl Streep and

Goldie Hawn who also withdrew. During this time of protagonist uncertainty,

Geena Davis was heavily campaigning for either role. Scott liked her, but did

know for which part, feeding rumors about her being able to take either part if

casting took too long. Her chemistry

with Sarandon clinched it, and they were off to the races.

During

the production of the film, the lighting and framing of some of the driving

scenes were difficult. Much of which caused them not to be able to wear a lot

of hats and glasses as the camera always had to find their faces. Sarandon, who

did a lot of driving for many of the film’s shots, commented on how she was

instructed to keep the camera shot between the side mirror and Davis as she

drove.

In

one of the insert essays for the immaculately sensuous 4k

Criterion Blu-Ray release of Thelma and Louise, film

critic Jessica Kiang (2023) marvels at the way costume designer Elizabeth

McBride visually represents Thelma and Louise’s transformation through their attire.

At each act break, the wardrobe of each principal character expresses their emotional

state. In act one, both women are buttoned up and constrained, trapped in the

lives that they are (at this point) momentarily escaping for a weekend. The

inciting incident breaks both women, and afterwards, there is a change of

clothes. Eventually by the third act:

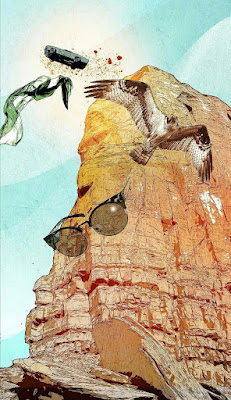

“The

makeup goes the way of the headscarves, which are replaced by battered hats

bartered or stolen from men. Plain tanks and sleeveless tees come to be favored

over girlish blouses and crisp shirts. Soon, the two rangy, tanned,

double-denimed redheads in the dusty blue Ford are almost camouflaged against

the stonewashed desert skies and the pink-orange sandstone bluffs”

(Kiang 2023).

The transformation of our principal characters is

visually expressed within the continuity of their clothes. They become unencumbered,

unfettered, freer… even as this is juxtaposed by the dangers getting closer as

the police close in. According to Khouri

(2011) they’ve went from invisible to, too big for the world to contain; all of

which is visually represented in t-shirts, jeans and sunglasses.[1] Indeed, the utter simplicity with which this

is visually conveyed in small increments, is so remarkable that it almost seems

meditative. Thelma and Louise are stripping off all the things that they were, to

embrace their new surroundings. They emerge out of their hardened gender

stereotypical shells revealing that they have taken on the aesthetics of the

geography of their liberation: the American Southwest.

Second Wave Representation and the Impact

on Third Wave Feminism

According

to Valenti (2007) Feminism can be

defined as:

1.

The belief in the social, political,

and economic equality of all the sex and gender identities within the gendered

spectrum that incorporates an understanding of standpoint differences based

upon age, race, class, disability, sexual orientation, cultural and religious

ideology.

2.

An organization and socio-political

movement around such a belief.

In discussing the overall

history of the Feminist movement, and to delineate the changes in scope, goals,

issues, and membership, several scholars and public intellectuals have organized

the movement into a “wave model”.[2]

During the development, shooting and release of Thelma and Louise, the

United States was on the precipice of its third wave of Feminism.

When

the public thinks of “The Feminist Movement” they think of “The Second Wave,” immortalized by names like Betty

Friedan, bell hooks, and Audre Lorde. “The Second Wave” feminist movement

coincided and overlapped with the Civil Rights movement beginning in the 1950’s.

Motivated by the renewed domesticity of Post World War II, women, particularly

white women, felt a non-specific malaise. This feeling was articulated by Betty

Friedan (1963) as “the problem that has no name.” to describe the state of

personal unfulfillment many women felt not having anything outside of embodying

the roles of wives and mothers.

“The most glaring proof that, no matter how elaborate, “Occupation

Housewife” is not an adequate substitute for truly challenging work, important enough

to society to be paid for in its coin…having their husbands share the housework

didn’t really compensate women for being shut out of the larger world.” (Friedan 1963: 350-351).

This state of “profound unfulfillment” motivated the second wave feminists

to fight for women’s ability to work outside the home, reproductive rights,

abortion rights, representation in government, and rights to education; and

against: the wage gap, sex discrimination, body image, hyper-sexualization, and

sexual violence. This ultimately led to such victories as contraception access,

equal pay acts, and federal body rights for women. These became the foundation with

which women and their allies could build a third movement.

Third

Wave Feminism rose to prominence through the fighting back against the

anti-feminist movement that rose out of the hyper conservative corporate

cultural flavor of 1980’s individualism (Hyde Amendment, Bombing/ defunding of

abortion clinics, murdering of abortion doctors). By 1987 85% of clinics

provided no abortions. It was a culture

where Feminism became known as “The other F-word.” The Third Wave

Feminism officially began during the outrage over the Anita Hill and Clarence

Thomas scandal. This controversy, coupled

with the shaming of Hill and the eventual appointment of Thomas to the Supreme

Court, energized feminists into a new movement, sparking Rebecca Walker to coin

the term "Third Wave” in 1992.

The

third panel of this Feminist Movement triptych, focused on the topics of

language re-appropriation, body and sex positivity, intersectionality (problems

and different realities living within a gendered system), social justice representation

in popular culture, sexual harassment, rape culture, LGBTQAI rights, and "Girlie"

Feminism.[3] At

the time, this burgeoning new wave, bursting with youth and vitality (as all

movements are initially) claimed many victories. They successfully staved off the

weakening and repeal of Roe (something that would remain commonplace until its

eventual repeal with the Dobbs decision in June of 2022). They helped to

pass and implement the Sexual Harassment ban by creation of a ‘hostile

environment’ in 1986. 1992 was deemed "The Year of the Woman", which

saw the election of the most women elected to congress in US History at the

time. Third wave feminists championed the federal ban against raping your wife in

1993, The Family Medical Leave Act 1993, the Violence Against Women Act 1994,

and the illegality of FGM (female genital mutilation) in 1997. In popular

culture, we also saw an increase in Feminist Icons: Madonna, Queen Latifah,

Angelina Jolie, and characters like Buffy Summers and Xena, who like Thelma and Louise were not only feminist icons, but were

also Queer claimed.

“We don’t live in

that kind of world Thelma.” Louise

In Thelma and

Louise, Thelma’s story arc is one that demarcates the transition from

Second wave feminism, to the more radicalized third wave. In the opening of the film, Thelma is the isolated

and embattled housewife Friedan (1963) describes above. Marrying Darryl right

out of high school, Thelma has little of an identity outside of the one she has

cobbled together behind his back, primarily through her friendship with Louise.

As the road trip begins, having never been on a vacation (presumably without

her Husband) and not knowing what to pack, Thelma brings (almost) everything.

Not knowing how to act, Thelma also begins to imitate Louise, playfully smoking

a cigarette and declaring: “I’m Louise.” like a child copying their parent’s

behavior to learn how to be an adult. This infantilism of Thelma continues when

she suggests stopping for a drink before they continue to the cabin. The

acquiescence of Louise is framed more as the capitulation of a mother to her

daughter rather than another adult. “Ok, but it’s gonna be a quick stop.”

Louise amends. An enraptured Thelma becomes a giddy schoolgirl bouncing in her

seat.

Thelma’s

innocent, open and naïve nature becomes a plot device that moves the story forward;

being the catalyst for the inciting incident and bridging the different acts of

the film. Because of this, cheap, easy, and intellectually uninteresting

criticisms full of victim-blaming were lauded at the film upon release in 1991.

Rather, what Thelma’s arc depicts is the persistent virulence of a misogynistic

rape culture that does not allow women to be open, honest, and trustworthy;

without being harmed for putting that faith in people. This messaging was

unfortunately drowned out in the public consciousness of the 1990s that saw

Thelma’s victimization as a catalyst to grasp feminist power, which now has become

a tired trope hung around the neck of every “strong female character” since. The

public takeaway of Thelma’s attempted rape (and the implied rape Louise experienced

in Texas) was not just that the patriarchal misogynistic cesspool of our

culture destroys our belief in humanity (framed by Thelma’s feminized

innocence); but that we need to break women of their femininity in order to make

them worthy of (Masculine) power. Thus, after the attempted rape, Thelma baptizes

herself in sex with a young robbing drifter, JD (Brad Pitt) and becomes born

again. And after surviving the crucible of his sudden and inevitable betrayal

(he steals their money) she is reforged into a liquor store robbing, cop

threatening, truck exploding badass. Thelma, like Louise before her (in Texas),

morphs from a second wave archetypical cautionary tale into a third wave

paragon. “This is what a (third-wave) feminist (will) look like.”

SOCIAL ANALYSIS

A lot has been written about Thelma and Louise since its release. The initial criticism of the film by critics were eventually drowned

out by the reclamation of the film in the eyes of the public. It is daunting to

write about a film that is so much a part of the cultural and socio-political zeitgeist. A film that is

used as a bridge between two subsequent eras of feminist liberation signifying its transformation without

becoming overwhelmed and a pedantically glib facsimile of other work that is better

written and researched. The film is even a part of academic discourse.

However, what seems to be missing in this discourse is a deconstruction

of the patriarchy through an analysis of the film’s male characters, a focus on

Adrianne Rich’s “The Lesbian Existence” not just through its queer reading (though

we’ll talk about that kiss), but through the importance, and power of female

friendships, and the main character’s liberation through masculinization that

echoes the wisdom and warnings of Audre Lorde.

“You

get what you settle for.”- Louise

Patriarchal

Takedown: The Men of Thelma and Louise

The

male characters of Thelma and Louise are a cinematic rebuke of the misogynistic

institutional shackles of marriage, family, and masculinity itself. From the

extremes of Thelma’s husband, Darryl, to the Arkansas Detective, Hal, with

Louise’s beau Jimmy, and honey trap JD in between. Each man represents a

certain type of masculinity and how those masculinities co-exist (or not).

For this purpose, Masculinity can be defined as:

…simultaneously a place in gender

relations, the practices through which men and women engage that place in

gender and the effect of these in the body experience, personality and culture

[through] everyday conduct of life…in relation to a reproductive arena defined

by the bodily structures and process of human reproduction. (Connell 1995: 71).

Darryl is the

embodiment of the masculine stereotypes within the institution of marriage: a bumbling,

philandering, oafish, meanspirited man, who barely rises to meet his own

mediocrity. He is the archetype of a common and likely story: he peaked in high

school, and imprisoned a smart, capable excitingly vibrant woman with the

chains of matrimony. Additionally, because

traditional masculine gender socialization has robbed him of any knowledge of

how to care for himself, or others, (he is a selfishly poor lover); he begins

to fall to pieces once Thelma leaves. In other films, where this device is

often employed to allow a (usually male) character to achieve an epiphany; and

learn to treat their spouse with more care and attention, Darryl doubles down

(albeit meekly) and attempts to use anger and threats to get Thelma to

comeback, a tactic that, prior to the events of the film, would have worked. While

this depiction is more believable than a sudden transformation that populates

other (lesser) films, it also points to the way that masculinity only allows

men to express the complexity of emotions through anger. He is scared,

distracted and utterly clueless without a woman to guide him. As the final

chase begins to escalate to its climax, we cut to Darryl one final time and

push in on his void and vacant face. He is dumbfounded. He is lost.

Jimmy is the epitome

of Masculine domestic violence. He classically fits into the behaviors of the

power and control wheel of sexual violence.

He is sweet and caring one minute, explosively violent the next. He is willing

to help wire some money to Louise (out of her own account). But when she goes

to pick up the money, she also finds Jimmy, because his help always has strings

attached. He sternly banishes JD and sidelines Thelma so that he can be alone

with Louise. In their hotel room, she doesn’t want to confide in him what

happened, so he violently throws a tantrum of an insecure man with arrested

development. When Louise rightly attempts to leave, he blocks her exit and gives

her an engagement ring. This whiplash reaction is common with domestic abusers

and is a textbook example of the cycle of violence.

Typical cycle of physical domestic violence

1) Unrealistic

Standards or expectations in the relationship (involves coercion)

2) Verbal abuse (yelling,

screaming)

3) Threat of Physical

attack (“I’ll kill you.” “Don’t make me beat the shit out of you”) which may

include destroying property

4) Actual Attack- One hit or multiple,

closed fist , open fist, with an object, sexual or not, doesn’t matter

5) Remorse from Attacker: minimizing/denying the attack and/or blaming

the victim. The police may or may not be called “It will never happen again”

6) Unresolved Action: Fear of leaving

attacker, forgiveness, internalizing blame, not pressing charges (Cycle then

starts over).

The morning after

the violence in the hotel room, Jimmy is back on the cycle in his remorseful

contrition stage; telling Louise that he won’t tell anyone where she and Thelma

are, where they are going, or that he’s even seen them. Louise blithely asks if

he took a drug that made him say “all the right things.” (implying that he

regularly doesn’t). It is in this moment of serenity that Jimmy, again, brings

up the ring. With the gentleness of talking to a small, wounded child; Louise

quietly says: “Why don’t you hold on to this for me.” And pushes the ring and

(metaphorically) him away. The last we

see of Jimmy is him being confronted by the cops to interrogate him about

Thelma and Louise’s whereabouts. Yet, unlike his promise, it is later revealed

by Hal that he told the cops everything that he knew. Whether that was a ploy to get Louise to come

back to him (assuming they were caught), or as punishment for her rejection of

him, remains to be seen.

JD is the female gazey incel that entices

naïve sex-starved Thelma into a romantic dalliance, so that he can rob her.

Thelma is clearly his target, setting up their meet cute for just after she

tells Darryl, in a phone call, to go fuck himself. In another instance, he leans

over while purposefully being backlit from the setting sun from Thelma’s side

mirror vantage point. All of this to trap her in a honey pot scam. However, unbeknownst to him,

Thelma is motivated toward the same passionate interlude to free herself from

the fear of the assault and attempted rape, so she can reclaim her body. JD’s

actions have a two-pronged effect: It complicates Thelma and Louise’s plans to

get to Mexico, forcing them to begin robbing from convenience stores and other people,

while it also provides Thelma with an (orgasmic) catalyst for her soulful and

spiritual awakening. The audience is left to determine if this nonconsensual

prostitution payment was money well “spent”[4]

Hal, the police officer, is the

film’s attempt at a male savior. In his initial investigation he believes that

the shooting was in self-defense, and in the face of mounting additional

evidence, supports them being brought in. He understands both Thelma and Louise’s

circumstances and what led them to make their decisions. At the end of the film, he is pleading with

the FBI field officer (Steven Tobolowsky) to not let the police shoot them, screaming:

“How many times does this woman [Louise] have to be fucked over?!” We last see

Hal as he desperately runs after the Thunderbird in vain, as it launches off

the cliff and into the Canyon.

The

last man in the film worth talking about is “Earl”, the truck driver. He is the

personified caricature of “toxic” masculinity’s sexual objectification of

women. Every encounter he has with Thelma and Louise on the road is disgusting.

He leers, hoots, hollers, makes obscene gestures, and verbally harasses them in

aggressively sexual ways. Yet, when they lure him to pull over, being an

oblivious imbecile who only sees women as things for his pleasure, he believes

he’s walking into a possible three way. Even when Thelma and Louise give him a

chance to apologize for his lewd behavior, he aggressively refuses. When they shoot out his tires in response, he

gets irater, prompting them to blow up his tanker truck in feminist cathartic

retaliation.

In looking at the intersections of masculinity, a greater light can be shined on these men when looking at their interactions with each other. Among them, Darryl is less confident, and preoccupied with cost and inconvenience, more so than his wife’s safety. In meeting him, Hal is so unimpressed that he just finds him comical, laughing at his antics and somewhat shocked by his ineptitude. Jimmy folds like laundry under the slightest police pressure, while clearly dismissing JD upon meeting him. It is also no surprise that Darryl, is the one to be cuckhold by JD. This is framed as the ultimate insult and the obliteration of Darryl’s fragile masculinity. As he is being led out of questioning, JD mentions to Darryl in passing: “I really liked your wife.” This sends Darryl into the most explosive tirade yet, having to be held back by four police officers from attacking JD, who from a comfortable distance away, begins to mock Darryl with sexually suggestive gestures. However, JD’s suave and swagger instantly crumbles when he is stuck alone in a room with Hal. Hal proceeds to treat JD like a sniveling child, berating and threatening him. Hal tells him: “If anything happens to them, I will hold you directly responsible for your part of it. Your ruin will be my God Damn mission in Life!” He, like Jimmy, acquiesces to Hal’s authority and masculinity.

Sometimes,

“The Lesbian Existence” is just “Friendship” 😉

The Feminist impact of Thelma and Louise cannot be

overstated. Regardless of the fact that the stars and filmmakers never intended to make an exclusively feminist film, the public ownership and social consequences as such, makes it one

(thank you WI Thomas). This feminism is empowered by

Thelma and Louise’s friendship.

In a Previous Essay, I explain Adrianne Rich’s “The

Lesbian Existence”:

In her article, Rich exclaims:

“Lesbian existence comprises both the breaking of a taboo and the

rejection of a compulsory way of life. It is also a direct or indirect attack

on male right of access to women. But it is more than these, although we may

first begin to perceive it as a form of nay-saying to patriarchy, an act of

resistance. It has of course included role playing, self-hatred, breakdown,

alcoholism, suicide, and intrawoman violence; we romanticize at our peril what

it means to love and act against the grain, and under heavy penalties; and

lesbian existence has been lived (unlike, say, Jewish or Catholic existence)

without access to any knowledge of a tradition, a continuity, a social

underpinning. The destruction of records and memorabilia and letters

documenting the realities of lesbian existence must be taken very seriously as

a means of keeping heterosexuality compulsory for women, since what has been

kept from our knowledge is joy, sensuality, courage, and community, as well as

guilt, self-betrayal, and pain”

As the term "lesbian" has been held to limiting, clinical

associations in its patriarchal definition, female friendship and comradeship

have been set apart from the erotic, thus limiting the erotic itself. But as we

deepen and broaden the range of what we define as lesbian existence, as we

delineate a lesbian continuum, we begin to discover the erotic in female terms:

as that which is unconfined to any single part of the body or solely to the

body itself, as an energy not only diffuse but, as Audre Lorde has described it,

omnipresent in "the sharing of joy, whether physical, emotional,

psychic," and in the sharing of work; as the empowering joy which

"makes us less willing to accept powerlessness, or those other supplied

states of being which are not native to me, such as resignation, despair,

self-effacement, depression, self-denial[7]

Rich identifies in this stitched together passage, (as in the article as

a whole) that in a patriarchal system women are taught to see other women as a

source of contention and competition for male attention (Thus making

heterosexuality compulsory through socialized behaviors, reinforced by rewards

from social structural institutions (Marriage, family, Military economy etc.)),

and denying the reality of the power women have among and with each other by

placing undue emphasis on the type and nature of a relationship rather than

what that relationship provides for the individuals involved. Thus, women are

socially trained through compulsory heterosexuality and patriarchal oppression

that the most important relationships that they have are with men, and that all

other relationships are secondary within this structure.

The journey that Thelma and Louise go on, is

one that sees a relinquishing of their primary relationships with men, while

understanding “the lesbian power” of their relationship with each other. The

arc of both Thelma and Louise is one of amalgamation. Throughout the course of

the film, they blur and blend into each other; becoming the same unified person,

together in the same place, just by different roads.

Thelma, in the

beginning of the film, actively looks up to Louise and sweetly emulates her because

she has no other role models, or really any relationships outside of

Darryl. Thelma’s journey is punctuated

by the lines of dialogue said to her that she repeats in a different

context. The first time that she stands

up to Darryl she uses the words Louise gave her, and when she decides to hold

up a convenience store, she cribs word for word what JD said to her the night

before. Through these experiences,

Thelma becomes harder and a little less trusting. Whereas Louise’s edges soften

a little and she becomes more introspective (Syme 2023). However, the credit

and power of the “Lesbian Existence” is displayed when Thelma and Louise have these

heartfelt exchanges:

One

Louise: I think I fucked up. I think I got us in a situation where we both

could get killed. I don’t know why I didn’t just go to the police right away.

Thelma: You know why. You already said.

No one would believe us. We could still get in trouble, still have our lives

ruined. You know what else, that guy was hurting me. If you hadn’t come out when

you did, he would have hurt me a lot worse, and probably nothing would have happened

to him because people saw me dancing with him all night. They would have made

out like I asked for it. My life would have been ruined a heck of a lot

worse than it is now. At least now I’m having some fun, and I am not sorry that

son-of-a-bitch is dead, I’m just sorry it was you who did it and not me.

___________________________________________________________________________

Two

Thelma: I know this whole thing was my fault!

Louise: Damn it, Thelma! You should know by now that none of this was your fault!

Thelma: Louise, I want you to know whatever happens, I’m glad I came with you.

_______________________________________________________________________

Three

Thelma: I guess I went a little Crazy, huh?!

Louise: No, you were always this crazy. This is just the first time you’ve had

to really express yourself.

___________________________________________________________________________

These examples are of two women supporting each other,

validating their choices, and moving in lock step with each other. After the film’s release, Thelma and Louise

became the paragons of female friendships for its audience. As they clasped

their hands and rocketed into the Grand Canyon, they were subsequently launched

into the future. It is not much of a stretch

to think if you mined the Photo albums of the late 90’s, they would show women,

best friends, sisters, lovers (possibly unrequited) jumping off sand dunes,

diving boards, out of planes, or the faces of cliffs, mimicking the final

moments of the film in solidarity with Thelma, Louise, and all women. This

moment is so powerfully iconic, that it has not only been recreated in the

lives of many young people at the time, but across popular culture.

Queer Coded and Claimed

When

looking at the basic plot structure of Thelma and Louise, it is obviously

a queer coded story. A quick and easy queer reading of the story could be: Two

women, unsatisfied with their lives with their heterosexual male partners, decide

to go off for a weekend alone. As they leave their lives behind them and begin

to relax, they are haunted and hunted by the heterosexist white male patriarchy

in the forms of a would-be rapist, Truck driver, and the army of police and

federal agents after them. The story that unfolds is allegorically damning

their love and annihilating their existence. First, they are enticed with the

bait of the heterosexual female gaze, in the form of JD. Then, the patriarchy

tries overt objectification through the Truck Driver. But at every turn Thelma

and Louise choose resistance and coupleship, each refusing to leave the other’s

side. In the final moments of the film, when the police are ready to assassinate

them, to put an end to their queer subversion; Thelma and Louise know that if

they surrender and are somehow not murdered by the army at their back, that

they will be separated, never to see each other again. Rather than life in a

heterosexist patriarchal cage, torn from the one they love, Thelma and Louise choose

love and death on their own terms. With their fate decided, the passion they

have held for each other finally breaks free of its heteronormative bonds and

they share a short but intense kiss of romance, recognition, and resolve. They

choose love over the cage that was their former lives.

Examples of Queer Coded Dialogue:

One

Thelma: You’re not gonna give up on me, are you?

Louise: Thelma, I’m not making any deals.

Thelma: In a way I get it, that way you’ll have something to go back to [beat]

with Jimmy.

Louise: Jimmy’s not an option.

Thelma: Listen, something has…crossed over in me. I just can’t go back.

Louise: I know. I know what you mean.

___________________________________________________________________________

Two: (very next scene)

Thelma: You awake?

Louise: I guess you could say that; my eyes are open.

Thelma: Me too, I feel awake.

Louise: Good.

Thelma: Wide awake. I don’t remember feeling this awake, you know what I mean?

Everything looks different. You ever feel that way, like you have something to

look forward to?

Louise: We’ll be drinking Margaritas by the sea, mamacita.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Three:

Thelma: What are you doing?

Louise: {Loads and chambers her pistol] Look, I’m not giving up.

Thelma: Ok, then. Listen, let’s not get caught.

Louise: What are you talking about?

Thelma: Keep going.

Louise: What do you mean?

Thelma: [Gestures to the cliff] Go.

Louise: [Smiling and Crying] You sure?

Thelma: [Nods] Yeah. Yeah.

Louise Grabs Thelma and Kisses her.

____________________________________________________________________________

One of

the reasons this dialogue can be queer coded and not explicit is due to the

historical time period of its release. At the time of the film’s production, in

the US, gays and lesbians were scapegoated into being the cause of the AIDS

epidemic, labeling it “the gay plague”. With the moral objection to non-heterosexual

sexualities increasing as AIDs case numbers rose, mainstream popular culture

was reticent to explicitly provide open and direct queer representation without

fear of reprisals.[5]

Therefore, the LGBTQAI+ community had to comb film, TV, music and other popular

culture for subtextual breadcrumbs in order to satisfy their hunger. Yet, even today,

while the Queer community are not starving for representation, they have never

had a full meal. In 2021, the annual GLAAD

report on representation in media found that only 20.8% of films that year contained LGBTQ

characters. However, this was not equally distributed throughout the group.

Most of these characters were gay men with Bisexual and Trans people having the

least representation among them. This decreased even further when the report

factored in race and had no representation of non-heterosexuals with

disabilities. Secondarily, even when representation is achieved it is usually

in declaration only. Many gay characters today are not allowed to be gay.

Even with 20% representation in 2021, far fewer numbers are also showing

affection, the dating process, romantic rejection, fights, and reconciliation.

Basically, being gay without showing it. At least with Thelma and Louise we got a kiss

before dying… That’s more than some studios will allow, even today. [6]

Thelma

and Louise: Appropriating tools to knock down the House

In a heterosexist

white male Patriarchy the escalation of violence is the result of noncompliance,

not compassion and empathy. Therefore, what started out as a clear action of

self-defense, accelerates into an inter-state chase, robbery, and assault,

because the Masculine institution of The Criminal Justice System can not be

compromised with, nor will it reckon with its misogyny and rape culture, the

components of which, are the reason Thelma and Louise decided to flee in the first

place. When developing the film, writer Callie Khouri talked to police officers

and asked them what would be said to alleged criminals once cornered.

She put their response

in the film, verbatim:

Any failure to obey

our commands will be considered an act of aggression against us.

She might as well have had the police say “Signed, “The

Patriarchy””

As Thelma

and Louise slough off their traditional femininity (Thelma more so than Louise)

and break free from the patriarchal power and control that has ruled or

overshadowed their lives for so long; they also begin to accumulate items,

behaviors and attitudes that are more masculine. With each set piece in the

film, they shed a little more of tradition, and move away from acceptable femininity.

As stated earlier, this can be read as the adoption of a gender fluid and queer

coded context. But it also can be seen as an attempt to use the tools of the

oppressor against them. Couple this with the uncompromising nature of the

system, and the result is when an unstoppable force (Unbridled Feminism) meets

an immovable object (The Patriarchy). Unfortunately, Thelma and Louise learn that

the more they push back against the carceral system and actively resist using

the tools of violence they have acquired, might keep them going, but it won’t

provide liberation.

Audre Lorde (2007) said it best:

“The Master’s tools will never dismantle the Master’s

house. They may allow us to temporarily beat him at his own game, but it will never

enable us to bring about genuine change.”

Thelma and Louise

aren’t changing the world with their actions, they are just trying to eke out an

existence based upon the terrible choices they have been given. As horrible as choices can be, like the

choice between getting shot or driving off a cliff, bad; you still have to make

them. Thelma and Louise choose the latter, because even though the master’s

tools won’t ever dismantle the master’s house, it doesn’t mean that you have to

live there.

CONCLUSION

Thelma and Louise is an iconic Feminist Masterpiece.

A generation later, it is still inspiring and foundational to both

individuals, communities and causes. The

more you watch, the deeper the analysis and appreciation goes. The filmmakers

believed that they cracked a glass ceiling with the success of this film and

that more films like it would flow from the breech. While we have seen a steady

increase in female led films in a variety of genres, there has never been

another Thelma or Louise. They remain frozen in mid-air on their pedestal,

daring us to follow them.

REFERENCES

Connell R. W. 1995. Masculinities California: University of California

Press

Friedan Betty 1963. The

Feminine Mystique New York: W.W.

Norton and Company Press

Khouri Callie 2011. “20th Anniversary Edition: Callie Khouri Looks Back

on Thelma & Louise.” In Script Magazine retrieved at https://scriptmag.com/features/20th-anniversary-edition-callie-khouri-looks-back-on-thelma-louise

Kiang, Jessica 2023. “Three Routes through Thelma and Louise: How The

West Was Won.” New York: The Criterion Collection

Lorde, Audre 2007. “The Master’s Tools will Never Dismantle the Master’s

House.” Sister Outsider California, Crossing Press

Scott, Ridley 1991. Thelma and Louise MGM

Syme, Rachel 2023. “Three Roads through Thelma and Louise: Bringing

to Life.” In Current New York: The Criterion Collection

Valenti, Jessica 2007. Full Frontal Feminism: A Young Woman’s Guide to

Why Feminism Matters New York: Seal Press

[1]

I’ll come back to this idea of clothing again in Social Analysis

[2] There

is a legitimate argument against organizing feminism into particular waves

According to Rory Dicker (2008):

"Approaching

Feminism as a collective project aimed at eradicating sexism and domination

seems the most practical way to continue feminist work. Quibbling about which

wave we are in now or in whether I think of myself as a second, third, or

fourth waver hardly seems a good use of my limited time; instead, I'd like to

see sustained feminist activism performed by young, middle-aged and old

women-separately or better yet, together."

[3] An

attempt to reclaim feminine beauty and body norms as feminist and not just a

symbol of traditional patriarchal gender norms.

[4] Plus,

it would take A LOT more than $6000 to sleep with Brad Pitt nowadays

[5]

Much of the direct queer representation came a little later in the 90’s but

were mainly independent films

[6] I

am looking at you Disney! Also, does that count as a “Bury your Gays”

trope if the Queer representation is coded and claimed rather than explicit?